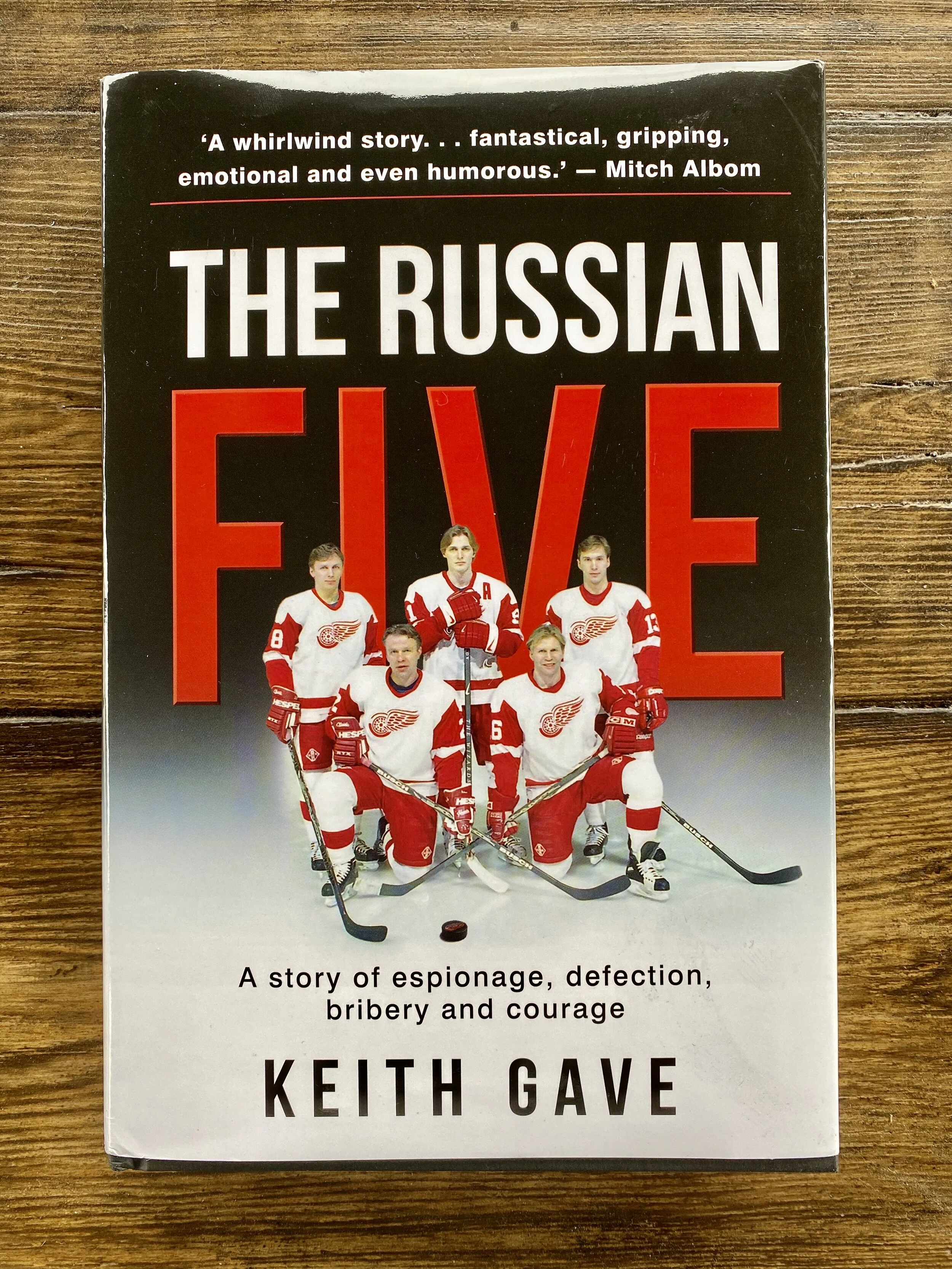

Lessons From “The Russian Five” by Keith Gave

As kids, my friends and I half-skidded, half-staggered across a variety of perilous and uneven ice-covered surfaces: the parking lots, streets, and playgrounds of mid-Michigan. We played something resembling hockey. There weren’t any youth leagues in our town then, so we made our own, complete with goals carved into snowbanks.

And we impersonated our heroes, the best players from our favorite team: The Edmonton Oilers.

Edmonton?

Yes, of course. The Oilers were the best, with Wayne Gretzky, Paul Coffey, Jari Kurri, and Grant Fuhr in goal.

We paid no attention to our state’s team, the Detroit Red Wings, because they were awful, and better known as “The Dead Things” in the mid-1980s.

“The Russian Five” is about how all of that changed: how the Red Wings built a transcendent and lasting success out of the ashes of the Dead Things era.

It wasn’t easy. It wasn’t conventional. And it certainly wasn’t linear, with fits and starts, advances and retreats, and adjustments and alterations on the way to title contention and, eventually, Stanley Cup championships.

Much more than a nostalgia trip, “The Russian Five” is a book about creativity, boldness, and perseverance in the face of criticism and uncertainty. It’s about operating without a road map and pressing on anyway.

In other words, “The Russian Five” is a book about how to build something great.

Espionage on the ice

The author, Keith Gave, is uniquely qualified to write this book. After all, he had an insider’s view as the Red Wings beat writer for the Detroit Free Press.

But the beat writer’s job wasn’t Gave’s only advantage.

Gave previously worked as a Russian linguist for the National Security Agency. And, without crossing ethical lines, he earned an assist by helping the Red Wings get two transformational players out of the Soviet Union.

Gave was propositioned by Red Wings executive vice president Jim Lites to pass along a message to Sergei Federov and Vladimir Konstantinov:

“You know hockey, you know the league, and you know us,” Lites said. “And as a member of the media, you can get access to those guys when nobody else in the NHL can. All we’re asking for is that you make that first contact for us. We can take it from there - if it’s going to happen - but we can’t do anything without that initial contact.”

While covering games in Helsinki, Finland, Gave was able to slip letters, tucked into media guides, from the Red Wings to the players—even as the KGB watched nearby. It was the opening salvo in what would become a pipeline of talent from the Soviet hockey team to Detroit.

Lessons learned

The Red Wings management, owner Mike Illitch, executive vice president Jim Lites, and general manager Jim Devellano, desperately wanted to revive the proud franchise, which bottomed out in the 1980s.

And we can learn from that time--from looking at the bold strategies and actions the Red Wings took--and apply them to our own work and lives today.

The standard approach wasn’t working

The Wings were building up, slowly, in the usual hockey fashion: by drafting North American players and adding a free agent here and there.

But the well-worn path wasn’t working, or wasn't working fast enough:

“But building through the draft is a painfully slow process, and it comes without a guarantee. It takes immense patience and more than a little luck -- borne through years of scouting and stockpiling and developing players who were teenagers barely shaving when they were drafted onto their NHL teams.”

If the Red Wings were going to succeed, the leaders would have take a new, unconventional, and even potentially dangerous path to tap a vast reservoir of previously unavailable talent.

“The quickest way to catch up, Devellano was now convinced after numerous briefings from Smith, was to begin drafting Europeans, especially those groomed behind the Iron Curtain.”

In 1989, the Red Wings selected Sergei Federov in the fourth round of the NHL draft. Using a high pick on a Soviet player just wasn’t done, because there was no precedent for getting a player out of the country and into the NHL.

Eventually, through defections and trades, the Red Wings would assemble five extremely talented players from the Soviet Union national team, reuniting them in Joe Louis Arena where they would eventually win a cup together, and kick off a enduring run of excellence. Forwards Sergei Fedorov, Igor Larionov and Vyacheslav Kozlov, and defensemen Vladimir Konstantinov and Viacheslav Fetisov ,brought the Stanley Cup back to Detroit.

No one succeeds alone

Bringing the Russian players to Detroit required a lot of help from both inside and outside the Red Wings organization.

Scouts had to implore Devellano to take that first bold step, drafting Federov in the fourth round in 1989.

Keith Gave delivered the opening communication to Federov and Konstantinov.

And the Wings needed a man on the inside, someone close to the team that would help convince the players to leave and guide them through their defections:

“There, Lites met a man pushing 50, a Russian ex-pat who had left his country when he was in his 30s. Because he spoke Russian, French, and English, the Soviets used Ponomarev as their official photographer whenever they are in North America or Western Europe. “I can talk to the guys for you,” he told Lites, who was beginning to feel like he could make the kind of deal that would pay enormous dividends for the Red Wings.

“As Mike Illitch told me over and over and over, always close,” Lites recalled. “So I sat there and said, ‘Let’s talk. If we do this, you have to work for me. I have to know your loyalties are to us.’ Their handshake deal was followed up with a written contract that said the Detroit hockey club would pay Ponomarev $35,000 for a successful defction of Sergei Fedorov or Vladimir Konstantinov.

‘And Michael, from that day on, was my guy. That’s how all this started.’

Success is always a team effort.

Let talented people flourish

Scotty Bowman is arguably the greatest coach in NHL history. He won nine Stanley Cups between 1972 and 2002, amassing 1,244 wins—more than any NHL coach in history.

Bowman was tough, demanding, and a control freak. But even he knew when to let talent flourish, such as when he put all five Russian players together on the ice.

As captain Steve Yzerman recalled:

“When (Coach) Scotty (Bowman) put them all together, the five Russians, there was instant chemisry,” he said. “It was unique. It had never been done in the NHL, and for us it was enjoyable, really enjoyable to watch, and obivously it helped us win hockey games.”

Slava Kozlov:

“Our biggest privledge was that the coaches didn’t touch us or try to teach us how to play hockey,” Kozlov said. “We were amongst ourselves and would talk to each other. I was actually shocked by the other guys. I adjusted not to what the coaches were saying but to what the guys were saying. I would do everything that my older partners told me.

[...]

Kozlov spoke without an ounce of bravado. Conceit, arrogance self-aggrandizement -- whatever you care to call it -- just isn’t in his DNA. Like theothers in the Russian Five unit, he was a “Master of Sport” in the Soviet Union -- and had the medal to prove it. When he said the coaches just let them play their game without getting in the way, he was merely confirming the same truth that Scotty Bowman spoke.

Strong leaders know when to let those they lead take the forefront--and everyone reaps the rewards.

Perseverance is critical: the journey is never linear

The Red Wings eventually became extremely successful--in the NHL’s regular season. But the playoffs continued to disappoint:

The Red Wings had begun a new season in the autumn of 1996 with a cloak of despair draped over the team. The fans sensed it, gripped by a malaise that was starting to feel comfortable. No longer were they giddy with hope and expectations. They had grown disillusioned after four straight spring times wrought with profound disappointment. Beyond wary, they were building a barrier around their hearts to keep them from being broken yet again.

Players, too. Captain Steve Yzerman was beginning to doubt that it was in the cards to have his name engraved on the Stanley Cup.

But the Red Wings did break through, hammering the Philadelphia Flyers in the 1997 Stanley Cup Finals, and rallying around a statement-making check by Konstantinov on the Flyer’s Dale Hawerchuk:

Hawerchuk, a Hall of Famer, left the ice, didn’t return, and retired after the series. Konstantinov’s hit—a clean check—was a clear declaration that 1997 would be different for the Red Wings, who went on the win the Cup.

Remember to savor the journey

Just six days after the Red Wings finally won the cup, tragedy struck.

Returning from a night out with his teammates, Vladimir Konstantiov and Slava Kozlov were in a horrible limousine accident.

“There’s been an accident,” he said, explaining that the caller was an officer from teh Oakland County Sheriff’s Department. No one said a word. Instead, they clusgterred aroudn their captain, who stuck a finger in his ear to block teh surrounding noise.

[...]

The Stanley Cup, until that moment the epicenter of their universe, was quickly forgotten. Ignored. Reudced to a gratuitious postscript.

Koslov recovered. Konstantinov survived, but would never play hockey again. Today he lives in Detroit and continues his therapy, more than 20 years later:

Ten months later, on an unseasonably warm March day, “the greatest hockey player in the world” lurches into the living room of his town house in suburban Detroit, grasping a walker. He has returned from a visit to his doctor and is accompanied by one of the nurses who provide round-the-clock assistance. He plops into a chair at a table off the kitchen to play a card game, Uno, with a Russian-speaking nurse. Irina Konstantinov says her husband really likes Uno. “The left frontal lobe,” she starts. “It handles executive functioning, where a person analyzes their own behavior, determines whether it’s right and appropriate. That he doesn’t have. Destroyed. He can’t process idealistic feelings about life, like love of country or happiness that his child is graduating. Everything for him is matter of fact.”

Photo: Det News

Chasing goals is great. But we have to remember to enjoy the climb as well. We never know what lies ahead.

Konstantiov’s legacy endures. The Wings became the gold standard in the NHL, winning championships in 1997, 1998, 2002, and 2008. His toughness and perseverance as detailed in “The Russian Five” is something we can all draw inspiration from.

“The Russian Five” is a fun and valuable read for any hockey fan

At times, Gave’s book reads like a 007 spy thriller, as the Wings schemed and smuggled players out from behind the Iron Curtain. At other times it’s a book about leadership, teamwork, tragedy, and belief in the face of uncertainty.

In any case, it’s much more than a sports book.

The Russian Five is a great retelling of the strategy, struggle, victory, and calamity of the Detroit Red Wings’ climb to greatness. The book’s lessons are applicable to all of us as we half-skid, half-stagger our way across the uneven and slippery surfaces of life.

You can pick up “The Russian Five” by Keith Gave at Amazon.

Detroit: An American Autopsy, by Charlie LeDuff

Writer and reporter Charlie LeDuff moved his family from Los Angeles back to his native Detroit, where he went to work exposing corruption, violence, and incompetence for the Detroit News.

And wow, was he busy.

“Detroit: An American Autopsy,” published in 2013, chronicles one of the more corrupt periods in Detroit history, during the reign of mayor Kwame Kilpatrick, who resigned in disgrace in 2008 before being found guilty of perjury and obstruction of justice.

Charlie is a talented writer who elicits powerful emotions in his readers: anger, disgust, and even despondency.

But he’s prone to some hyperbole, and seems resigned to declare the city dead—an understandable position, given what he witnessed and wrote about every day.

Thankfully, the intervening years have proven LeDuff’s proclamation false.

Detroit isn’t dead.

Yes, it has a long way to go, but justice did prevail in rooting out the corruption of the Kilpatrick regime, and the city continues to make strides.

LeDuff lays out a compelling case that Detroit’s troubles began in the 1950s:

Detroit actually began its decline in population during the 1950s, precisely the time that Detroit—and the United States—was at its peak. And while Detroit led the nation in per capita income and home ownership, automation and the beginnings of foreign competition were forcing automobile companies like Packard to shutter their doors. That factory closed in 1956 and was left to rot, pulling down the east side, which pulled down the city.

During and after the Great Recession, Detroit was a city dominated by fear, violence, graft, and incompetence. And this is no more evident than in the struggles of the city’s firefighters, up against impossible odds:

”Arson,” he said. “In this town, arson is off the hook. Thousands of them a year, bro. In Detroit, it’s so ******* poor that fire is cheaper than a movie. A can of gas is three-fifty and a movie is eight bucks, and there aren’t any movie theaters left in Detroit, so fuck it. They burn the empty house next door and they sit on the ******* porch with a forty, and they’re barbecuing and laughing ’cause it’s ******* entertainment. It’s unbelievable. And the old lady living next door, she don’t have insurance, and her house goes up in flames and she’s homeless and another *******block dies.”

[…]

The city, what’s left of it, burns night after night. Nature—in the form of pheasants, hawks, foxes, coyotes and wild dogs—had stepped in to fill the vacuum, reclaiming a little more of the landscape each day.

As arson engulfed the city, Detroit firefighters dealt with substandard equipment, leading to unnecessary danger and death:

As the firemen were snuffing out remnant embers in the attic, someone heard timber snap. And then the roof collapsed. “He was right behind me,” said Hamm, pointing to the spot. “He was right next to me. I don’t know why I’m here.” It took a few minutes to find Harris because his homing alarm failed to sound. It failed because it was defective. Because that passes for normal here. Defective equipment for emergency responders. Harris died not because he was burned or because the timber broke his bones. He died of suffocation, unable to breathe from the weight of the roof. If the alarm had only worked.

City firefighters were the victims of inadequate funding as elected leaders and bureaucrats skimmed dollars off the budget for themselves.

But even by Detroit standards of corruption, Monica Conyers, city council member and wife of late congressman John Conyers, stood out:

The madam city council president found herself denying to me and the rest of the press that her ex-con brother had gotten a no-show city job at her request. She denied, in fact, that he was her brother at all before turning around and admitting that he was in fact her brother.

[…]

Sensing she was near the end of her freedom and her threadbare sanity, I called Conyers on her cell phone to get an interview. No answer. I hung up. My phone rang a few moments later, a return call from the same number. “Monica?” “Who’s this?” the voice answered. “Charlie LeDuff.” A long pregnant pause. “Uhmmmmm . . . my name is Teresa,” the voice stammered. “Monica doesn’t have this number anymore.” “Jesus, you’ve got to be kidding me,” I said with a laugh. “Monica, I know it’s you. It’s your voice.” “No, this is Teresa. Sorry.” And then Monica hung up.

[…]

After months of denials, she finally admitted to shaking tens of thousands of dollars and jewelry from people with business before the city council and the pension board on which she served. The feds had it all—Conyers taking envelopes stuffed with cash, Conyers taking money from a businessman’s coat pocket, Conyers walking out on her meals without paying. Among the highlights of the wiretapped conversations played in court: “You’d better get my loot, that’s all I know,” Conyers told her aide-de-camp Sam Riddle at one point.

There are horrific and senseless tales of the worst aspects of humanity in this book. As LeDuff chronicles Detroit’s struggles, he weaves in tales of personal tragedy from his own past in the city.

The book is grim.

And yet even amongst the despair, there are moments of hope and inspiration.

LeDuff shares stories of people doing the best they can in absurdly difficult situations. The firefighters. The police. And citizens of the city, just trying to move forward:

But what you gonna do? You ain’t gonna be reincarnated, so you got to do the best you can with the moment you got. Do the best you can and try to be good. You dig?”

Time has put some distance between the events of the book and the current day, leaving enough space to see that hope remains for Detroit—precisely because of the people trying to do the best they could, and trying to be good.

You can pick up “Detroit, an American Autopsy,” at Amazon.

Ladies and Gentlemen, The Bronx is Burning, by Jonathan Mahler

“Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning,” is as ambitious, varied, and entertaining as the city it focuses on.

The book’s title, taken from a Howard Cosell declaration made on national TV during the World Series (as an abandoned building burned nearby), is pitch-perfect, so to speak.

New York City was a tumultuous, turbulent, and facinating place—not to mention pretty dangerous—in the 1970s, and no time moreso than 1977, the year which is the focus of the book. Nineteen seventy-seven was a year New York nearly broke down, and later, broke though.

ESPN liked the book so much it created a mini-series based on the New York Yankees’ ‘77 pennant chase.

The focus here is on so much more than just the Yankees, with a wide net cast to gather together all the components of a city in crisis:

Government social policy and budgeting

The debut of Studio 54

The emergence of punk rock

The histories and personalities of Billy Martin, George Steinbrenner, and Reggie Jackson

Urban planning theory

Terrorism

Rampant arson

The crimes, media manipulation, and eventual capture of serial killer Son of Sam

The strategy and politics of city zoning

The gentrification of SoHo

The blackout riots, looting, and police response to the New York City blackout of July 13, 1977

The electrical grid strategy of New York City

The 1977 mayoral race, candidates, and strategies

Highway planning

Even that list is incomplete. The book covers a lot of ground.

I won’t summarize the book here—there are too many topics. But I will share some insights from some of the major events within, and below the post you will find my Kindle highlights from the book itself.

The 1977 New York City Democratic Mayoral Primary

Amidst crime and financial disaster, four candidates, including Ed Koch, Mario Cuomo, Bella Abzug and incumbent mayor Abraham Beame, squared off in a bloody Democratic primary full of sniping, back-biting, and backroom deals.

But as vicious as the race was, I’m struck by the tone and content of Koch’s TV commercials.

Koch was seen as the most confrontational candidate, but these ads are so vanilla they would be ignored today:

Amazingly, Koch won the democratic primary running against the teachers and police unions, and taking a pro-death penalty stance. He sounds very conservative in these ads, which ran during the primary where he was trying to capture only left-leaning voters.

Koch went on to be mayor New York until the end of 1989.

George vs Billy vs Reggie

In 1977, Billy Martin was in the first of his four runs as Yankees manager, and many days it looked like he wouldn’t keep his job for the entire season. Martin, as mercurial as any manager who ever led a team, was sandwiched between his combustable and jealous owner, George Steinbrenner, and his preening and insecure superstar—who was new to town—Reggie Jackson.

Together, the three of them barked at each other in the press and in person, and schemed behind each other’s backs.

Famously, Martin and Jackson nearly came to blows in the Boston dugout after Martin pulled Jackson mid-inning following a Jackson flub in right field:

Martin not only kept his job after this incident, but the team rallied. The Yankees came from behind in the standings to overtake the Red Sox in the division and bested Kansas City in the ALCS before beating the Dodgers in the World Series.

The blackout of July 13, 1977

It’s not easy to make one of the world’s largest cities go dark, requiring a potent mix of circumstance and bad decisions:

A lengthy heatwave, pushing temperatures over 100, while tempers and demands on the power grid climbed right along with it.

Clean-air regulations pushed power plans well outside the city limits.

A tenuous feeder system bringing power into the city from those plants with too few lines and little redundancy.

Some lightning, taking out feeder lines.

Poorly maintained emergency generators.

A board operator who froze, failing to disconnect subsections of the city, which would have reduced the overall power draw into the city grid and prevented total failure.

The result was disastrous: the entire city went dark. Every borough.

Mass looting and fires followed in certain areas, particularly in the South Bronx and a subsection of Brooklyn called Bushwick.

As a result, an area of poverty and high unemployment destroyed itself—creating worse poverty and unemployment. Seven years later, the area was still rebuilding, as detailed in this 1984 New York Times article:

A tangible recovery is building in the bombed out heart of the neighborhood around St. Barbara's. It can be traced to construction of what amounts to a small village of public housing units, ordered by Mayor Koch at a cost of $58 million, and to a revival in a private real- estate market that has spilled over from the adjoining neighborhood of Ridgewood, Queens.

Little noticed by those outside Bushwick, this insular community has, along with sections of the South Bronx and some other parts of Brooklyn, become an example of a downtrodden community, seemingly at the end of its line, that for all its problems has quietly managed to negotiate an upturn.

[…]

''There has been a definite turnaround and it's going on just all over the place,'' said Elliott Yablon, director of the Bushwick Neighborhood Preservation Office of the city's Department of Housing Preservation and Development. ''I think it's own momentum is going to carry it through. If we walked away, the recovery might not be as planned, but it would happen anyway.''

Bushwick’s slow recovery was a microcosm of the entire city’s resurgence.

In 1977, New York seemed to be on the brink of collapse. And while many people thought New York was in its death throes, it was really going through birthing pains.

The restoration—of Bushwick, of law and order, and of the cities finances—snowballed into a renaissance for New York, the tailwinds of which still carry the city forward today.

Just another example that it truly is darkest—pitch black, even—before the dawn.

Photo by Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images

Book notes

(Kindle Highlights)

PROLOGUE

When I first embarked on this book four years ago, my intention was to write about the ’77 Yankees against the backdrop of New York during this infamous era of urban blight. As the months passed, though, the city slowly advanced into the foreground, and the two stories became one.

I gradually came to regard ’77 as a transformative moment for the city, a time of decay but of rehabilitation as well. New York was straddling eras.

PART ONE

1.

the thirty-seventh Democratic National Convention. The last two—Chicago ’68 and Miami ’72—had been notoriously rancorous, but this one was guaranteed to be a love fest. The party’s presidential candidate, the genteel Jimmy Carter, had already been anointed, and the city was primping for its close-up. Special repair crews were sent out to patch potholes in midtown, the Transit Authority changed its cleaning schedule to ensure that key stations would be freshly scrubbed for the delegates, and more than a thousand extra patrolmen and close to one hundred extra sanitation men were assigned to special convention duty. With the help of a hastily enacted antiloitering law, the police even managed to round up most of the prostitutes in the vicinity of Madison Square Garden.

2.

The clinical term for it, fiscal crisis, didn’t approach the raw reality. Spiritual crisis was more like it. The worst part was that Beame had seen it coming. As the comptroller to his predecessor, John Lindsay—the equivalent of being lookout on the Titanic, as the columnist Jack Newfield once quipped—Beame knew just how precarious things were.

“The man left us with a budget deficit of $1.5 billion,” snorted Beame, slapping the paper with the back of his hand for effect

By February ’75, Beame was supposed to have gotten rid of twelve thousand of the city’s three hundred thousand employees. A New York Times investigation revealed that only seventeen hundred were gone; the rest had merely been shifted to other budget lines.

Reminders of the city’s decline were already everywhere. In 1972 the Tonight Show had moved from midtown Manhattan to Burbank, California.

As for Beame, the time for tiptoeing was over. He gave thirty-eight thousand city workers, including librarians, garbage collectors, firemen, and cops, the ax. In anticipation of the layoffs, the police union had already distributed WELCOME TO FEAR CITY brochures at Kennedy Airport, Grand Central Station, and the Port Authority Bus Terminal,

Fear City also became Stink City when ten thousand sanitation workers walked off the job to protest the layoffs. The piles rose quickly, and ripe refuse was soon oozing from burst garbage bags and overstuffed trash cans,

Mayor Beame ended 129 years of free tuition at New York’s public colleges, including his alma mater, City College, the fabled gateway to middle-class life.

By the end of his second term Lindsay had become, in the words of one especially memorable magazine headline, AN EXILE IN HIS OWN CITY. Thus did Beame’s moment arrive. There was no seductive rhetoric, no risk of dashed expectations. He was New York’s rebound lover. What’s more, he was a bookkeeper, and New York’s books were in desperate need of attention.

3.

New York had been though hell, but in the summer of ’76 there was reason for hope. It was a feeling more than anything, palpable, if not quantifiable, that the embattled city was on the edge of a new day.

Los Angeles could have The Tonight Show; New York now had Saturday Night,

The counterculture was starting to migrate from San Francisco to New York, a trend evidenced by Rolling Stone’s plan to relocate from Haight-Ashbury to midtown Manhattan in the summer of ’77.

As for Beame, the pained expression that he’d worn for the better part of the last two years was finally giving way to something approaching a smile. “I think we’ve turned the corner and seen the light at the end of tunnel,” the Mighty Mite told reporters in the fall of 1976. By now the city had an election of its own approaching, the ’77 mayoral election.

4.

What Martin lacked in talent he made up for in grit. The same determination that had propelled this juvenile delinquent out of the sandlots of a dirt-poor, fatherless childhood near the docks of Berkeley—his grandmother had floated over from San Francisco with all her household possessions on a raft—drove him to overachieve as a big leaguer.

Martin would have done anything to avoid losing, but winning came at its own cost. In short, his emotional makeup was not equal to the pressure, external or internal, of playing so far above his head.

Martin fought insomnia, hypertension, and what was then known as acute melancholia. His churning stomach kept him from eating for long stretches. What he did eat, he’d often puke back up. Martin tried to cope, popping sleeping pills and drinking bottomless glasses of scotch, but nothing could quite cure the distemper.

They got it. Martin managed the game just as he had played it: personally, emotionally, intensely.

As the wins piled up, the stakes mounted, and the prospect of losing became that much more sickening. Martin, who was always skinny, was now more gaunt than ever. Over the course of the ’76 season, he shed 20 pounds from his six-foot frame, dropping to a mere 154. The crow’s-feet around his eyes, which had first appeared during his playing days, deepened.

The brand-new ballpark was in tatters. Huge chunks of turf were uprooted, every base had been stolen, and the field was littered with garbage, from newspaper shreds to empty bottles of Hiram Walker brandy and Jack Daniel’s. The Yankees had won their first pennant in twelve years.

to make matters worse, he and his second wife, Gretchen, a former airline stewardess and the belle of her sorority at the University of Nebraska, split up shortly after the season ended.

He spent the winter of ’76–’77 alone in the Hasbrouck Heights Sheraton

he was worrying about his teenage daughter from his first marriage, who’d been thrown in jail in Colombia after being accused of trying to smuggle cocaine out of the country in her panty hose.

5.

WHEN news of Rupert Murdoch’s purchase of the New York Post first hit the Daily News and The New York Times—the sleepy Post had been scooped on its own sale—on November 20, 1976, the city’s response was a collective “Rupert who?”

The Post’s own founding father, Alexander Hamilton, had himself never been one to underestimate the dark side of human nature, or what he preferred to call its “impulses of rage, resentment, jealousy, avarice and of other irregular and violent propensities.”

(Ernest Hemingway had the Post sent to him in Cuba so he wouldn’t miss the offerings of its emotional star columnist, Jimmy Cannon.)

the Post was soon faltering as well. By the middle of the seventies the very notion of an afternoon newspaper seemed antiquated, particularly now that Vietnam and Watergate, which provided daytime copy that seemed too urgent to wait until the following morning to read, were passing into history.

Earl Wilson was still dutifully filing “It Happened Last Night,” but by the middle of the seventies the column had come to seem quaint, anachronistic. The rest of the media were busy discovering the new celebrity culture: Time Inc. launched People, Andy Warhol launched Interview, the Daily News hired people spotter Liz Smith.

It’s hard not to read something else into the paper’s aimlessness. The trauma of the Lindsay years had eroded the populace’s faith in New York’s civic culture, which the Post had so assiduously nurtured with its expansive, old-fashioned liberalism. By the mid-seventies New York’s predominantly liberal middle class was becoming an increasingly conservative lot. Somewhere along the way the Post had lost its raison d’être, and Rupert Murdoch, who like any self-respecting publishing tycoon yearned to sink roots in New York, had apparently found his.

6.

At a few minutes past midnight Reggie Jackson stepped off the plane and into the bracing East Coast air with a blonde on his arm. The cameras were now rolling. A Grandstand reporter approached his six-foot, 207-pound subject and poked a microphone in his bespectacled face: “Welcome to New York, Reggie!” Jackson looked at the reporter, grinned, and asked, “What the fuck are you doing here?”

“I once had a long talk with Reggie about his childhood, and I asked him what he had gotten out of living in an upper-middle-class white neighborhood,” recalls Newsday’s Steve Jacobson. “He fiddled around with the question for a while and came up with ‘aspirations.’”

During Jackson’s sophomore year, his only season of varsity ball at ASU, he broke the school’s single-season home run record with fifteen. It doesn’t sound like much now, but at the time it was unheard of, largely because most colleges, including Arizona State, considered baseball a low priority and bought cheap, lightweight bats. He also became the first collegian to hit a ball out of Phoenix Municipal Stadium.

Reggie Jackson was the second player chosen in the 1966 draft. He might well have gone first, his coach at ASU informed him, had the New York Mets not been put off by a line in his scouting report that said he had a white girlfriend.

The following year, 1967, Jackson was bumped up to the A’s AA franchise in Birmingham.

Jackson spent a couple of weeks sleeping on the couch of the apartment of a couple of his white teammates, Joe Rudi and Dave Duncan. Rudi told Jackson that their landlord had threatened to evict them if “the colored” didn’t leave.

six hundred feet is only the estimated length of the one Jackson hit in the ’71 All-Star Game in Detroit.

The ball would have sailed right out of the ballpark if it hadn’t crashed into an electronic transformer on top of the roof in right-center, making the titanic blast only more dramatic; it looked as if sparks were actually going to fly.

“I wasn’t sure the first time I saw him,” Ted Williams said in 1970. “The second time I was amazed. He is the most natural hitter I have ever seen.”

Reggie adhered to a different motto: If you don’t blow your own horn, there won’t be any music. “When you take over a pitch and line it somewhere, it’s like you’ve thought of something and put it with beautiful clarity,” Jackson told a writer for Sports Illustrated, finishing the riff with a line that couldn’t have made SI’s headline writer’s job any easier: “Everyone is helpless and in awe.”

Everywhere they went, people were calling out to Reggie. “I had been there before, but I really hadn’t been there before. It was as if I had seen New York across some crowded room, caught her eye, but never got the chance to talk to her,” Jackson remembered in his 1982 autobiography, co-authored by Mike Lupica. “Now I was talking to her, feeling her. Being seduced by her.”

Reggie Jackson’s new manager, Billy Martin, followed the Steinbrenner-Jackson courtship in the papers with a growing sense of disgust.

But what bothered the fatherless Martin most was all the attention that Steinbrenner had lavished on Jackson. “George was taking Reggie to the ‘21’ Club for lunch all the time, and I was sitting in my hotel room the entire winter and George hadn’t taken me out to lunch even once,” Martin later complained in his autobiography.

7.

ON a cold, snowy night in the waning days of 1976, former New York congresswoman and noted liberal firebrand Bella Abzug summoned her closest confidants to her red-brick town house on Bank Street in Greenwich Village. After stomping the snow out of their boots and stripping off their overcoats, they filed into the parlor, which, with its worn velvet couches and peeling red paint, resembled nothing so much as a Venetian bordello. It was time to discuss Bella’s future. The question was whether she should run for mayor. Private balloting would have revealed a landslide against the notion.

The joke around Congress went that asking Abzug to sponsor a piece of legislation was the best way to ensure its defeat.

The only oppressed minority that Abzug had no sympathy for was her staff. It wasn’t just the twenty-hour days; it was the emotional torture in the form of expletive-streaked abuse.

8.

HAVING already gobbled up one New York journalistic institution, Rupert Murdoch was now hungry for another. His eyes alit on New York magazine.

As 1977 got under way, Rupert Murdoch took control of three major New York journalistic institutions,

9.

All winter the New York papers had been filled with speculation about how Reggie and Munson were going to get along. The forecast called for storms.

10.

IN all of Billy Martin’s years playing for Casey Stengel in the fifties, the Yankees had never put together a winning record in the Grapefruit League. Martin saw the logic inherent in this. The regular season was long enough.

It wasn’t to be. Not only did Steinbrenner expect his manager to win grapefruit games, but he didn’t like his living so far from the ballpark, nor did he approve of his driving to games instead of taking the team bus.

“I ought to fire you right now,” Steinbrenner answered. “I don’t give a shit if you do fire me, but you’re not going to come in here and tell me what to do in front of my players.” The players quickly rallied to Martin’s defense.

The Daily News’s Dick Young speculated that the Yankees’ owner had paid off kids and cabdrivers to yell out to Reggie when he first brought him to New York for lunch at ‘21.’

“If I lead the league in homers and runs batted in and win the M.V.P. award and we win the World Series, they’ll say, ‘He should have done that. Look what they’re paying him,’” Reggie told Murray Chass, the beat man for The New York Times. “If I don’t do it, if I come short of it, if we don’t win, it will be my fault. ‘Steinbrenner fouled up, Jackson’s no good, he hurt the club, he created dissension.’”

Reggie pointed out that the old Bronx Bombers were all white and that their front office was racist and bigoted. “They didn’t want no black superstars,” Reggie snapped, deliberately letting his usually proper grammar lapse for effect. He was hedging his bets: If he didn’t become a hero, at least he could be a martyr.

11.

AMBITION was about the only thing that Edward Irving Koch, the latest entrant into New York’s 1977 mayoral race, had going for him.

Only 6 percent of the city had any idea who Ed Koch was.

The few New Yorkers who did know Ed Koch in the spring of 1977 thought of him as a lumpy liberal from Greenwich Village. A middle child, he’d been born in the Bronx, though his parents, Jewish immigrants from Poland, had started their New York journey in a scabby, peeling tenement on the crowded Lower East Side. Koch’s

Sergeant Koch returned from the war in 1946, a heady time for middle-class New York. Mayor La Guardia’s handiwork was everywhere: prepaid health insurance for all New York residents; twenty-two municipal hospitals; subsidized housing cooperatives; a five-cent subway ride that zigged and zagged across four boroughs. La Guardia spoke endlessly about beautifying New York, about finding new ways to lift the spirit of its citizens. His successor, William O’Dwyer, picked up right where La Guardia left off.

When Koch ran in a local assembly race in 1962, he dubbed his platform “SAD” after its three linchpin issues: sodomy, abortion, and divorce. (He was for making gay sex and abortion legal and for rewriting the state law that considered adultery the only viable grounds for divorce.) Despite an endorsement from Eleanor Roosevelt, Koch got his clock cleaned,

but the following year he ran for district leader against the neighborhood’s longtime Democratic power broker, the man known as the Bishop, Carmine De Sapio.

Koch had won the election by 41 votes.

Koch clambered up onto the platform and cut through the racket. There was no time to celebrate. “This election can be stolen from us,” Koch said. “Every captain must return to the polls right away with an able-bodied man. See that those machines are not tampered with.”

few noticed that as the sixties wore on and the Village’s once-quiet streets became more crowded, Koch began absorbing some of the conservative values of longtime locals. He was evolving in small but portentous ways, as he reconsidered his position on local hot-button issues like the concentration of gay prostitutes on Sixth Avenue and the endless proliferation of noisy coffeehouses.

In 1968, Koch ran for Mayor Lindsay’s old congressional seat in Manhattan’s so-called Silk Stocking district.

Once he was elected, his friends told him to hunker down and become a ten- or twelve-term member of Congress,

Orange highlight | Page: 93

Koch, like Beame and Abzug, aspired to more. He’d dreamed of becoming mayor for years—“I

12.

the ’77 team was going to start five blacks. Center field, where DiMaggio, Mantle, and Murcer had once roamed, was the province of a young man from the Miami ghetto, Mickey Rivers. Second base belonged to rookie Willie Randolph, who had grown up in the Samuel J. Tilden housing project in Brownsville, Brooklyn. And the new right fielder was of course Reggie Jackson.

Reggie had other plans. One of Steinbrenner’s real estate mogul friends set him up with a $1,466 corner apartment on the nineteenth floor at 985 Fifth Avenue, a white-brick building just down the block from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

He was the only Yankee who lived in Manhattan,

As of mid-May, Reggie Jackson was hitting .250, with a mere five home runs.

13.

IN the middle of May, New York’s already crowded mayoral race absorbed one final candidate.

But where Mario Cuomo was concerned, most people who knew him were inclined to be charitable.

This, at least, was the picture of tranquillity that prevailed until 1966, when word spread through the community that the high school going up in nearby Lefrak City was going to force the condemnation of sixty-nine houses in Corona. The residents hastily mobilized and hired a thirty-three-year-old lawyer, Mario Cuomo, to help them take on City Hall. Four years and dozens of briefs later, the bulldozers were moving closer to Corona. Cuomo had exhausted his legal options with no visible progress. The whole business might have passed unnoticed into history—another community plowed under by City Hall, another idealistic young lawyer disillusioned along the way—had not a stocky, rumpled caricature of a newspaperman named Jimmy Breslin tumbled into the picture. One Sunday night in November 1970 a friend of Breslin’s persuaded the writer to come along with him to a Corona homeowners’ meeting at the headquarters of the local volunteer ambulance corps.

After the meeting Breslin took this man, Mario Cuomo, out for a cup of coffee.

With Breslin’s help, the so-called Corona Fighting 69 became a cause célèbre. Newspapers as far-flung as the Los Angeles Times editorialized in their defense.

In the end Cuomo decided not to run for mayor in ’73. He made his first bid for elective office a year later, losing the Democratic nomination for the lowly job of lieutenant governor. It was a humiliating defeat for a man with so much political promise.

Fortunately, the new governor, Hugh Carey, recognized that promise and asked Cuomo to be his secretary of state.

In early 1977 Carey came to Cuomo with a new task: running for mayor.

After a few months of hemming and hawing, Cuomo reluctantly agreed.

14.

Sport scheduled the story—REGGIE JACKSON IN NO-MAN’S LAND—for its June issue.

Several years later, when Reggie published his autobiography—in vintage fashion, he dedicated the book to his biggest fan, God—he claimed that the whole conversation at the Banana Boat had been off the record, and that he had been misquoted to boot.

15.

Such was the state of the rivalry, reborn anew for every generation, between the Yanks and the Sox, on the afternoon of May 23, 1977. If a pair of outfielders, Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio, had personified the battle in the 1940s and 1950s, the teams’ warring catchers did that day: the tall, even-tempered, urbane Carlton Fisk and the stumpy, grumpy, caustic Thurman Munson. Boston versus New York in a nutshell.

16.

ON the morning of June 16, 1977, the city woke up to the news that the Mets had traded Tom Seaver to the Cincinnati Reds.

The loss of Seaver felt like the loss of hope, not for the Mets, who already were hopeless, but for the city itself. It was more than the man; it was the moment the man represented, that improbable pennant run during the glorious summer of 1969, when John Lindsay owned New York and the city still felt full of possibility.

17.

A 1977 New York City Planning Commission report counted no fewer than 245 pornographic institutions in the city. In 1965 there had been 9.

Mayor Beame, who was old enough to remember when the marquees along West Forty-second Street billed George M. Cohan’s latest musical rather than “live nude girls,” had been vowing to “reverse the blight in this vital center of our city.” But between the loopholes in city and state laws, the dwindling number of city policemen and prosecutors, and the need to avoid violating the civil liberties of his citizens, it had not been easy.

In 1977, Times Square saw the opening of Show World, its biggest sex institution yet. Situated on the corner of Forty-second Street and Eighth Avenue, the heart of Times Square, Show World was a twenty-two-thousand-square-foot multistory sex arcade complete with video booths, live sex acts, and private rooms where naked women sat behind thin sheets of Plexiglas. Most sex emporiums were dark, mysterious. Show World, which announced its presence with a blinking neon sign, was bright, garish. Some four thousand people passed through its doors each day.

New York’s middle class was absorbing its appreciation for sexual excess not from Park Avenue but from the West Village. Sandwiched between the arrival of AIDS on New York’s shores during the 1976 bicentennial celebrations and the first reported cases of the virus in 1978, 1977 was the last great year of unprotected, nonreproductive sex in the city.

18.

Before entering politics, she worked as an attorney, defending alleged Communists—McCarthy called her one of the most subversive lawyers in the country—and a thirty-six-year-old black man who had been convicted of raping a white woman in Laurel, Mississippi, on whose behalf Abzug appeared in court eight months pregnant. Abzug became an early champion of gay rights during her 1970 congressional race,

Nothing got Abzug hotter than Westway, the city’s plan to rebuild the West Side Highway south of Forty-second Street. The blueprints called for burying the highway in a concrete tube beneath the surface of the Hudson, then extending the deck above out into the river to make room for parks and office and apartment buildings.

Naysayers needed only point to The Power Broker, Robert Caro’s magisterial 1974 biography of Robert Moses, to underscore just how destructive overzealous city planners could be.

She sponsored a clever piece of legislation that would enable cities to swap federal funds earmarked for interstate highways for mass transit money. Instead of getting $1 billion from Washington to build an interstate highway, New York City could opt for $550 million to rehabilitate its subway system, a needy case if ever there were one. Framed as a choice between automobiles and subways, between lining the pockets of real estate developers and improving the lives of workaday New Yorkers, Westway became a perfect foil for Abzug, who saw her beloved city as an overgrown village, a place where the power belonged to the people, not to the men with green eyeshades and pocket protectors who had the nerve to talk about the “greater good.”

19.

ON June 17, 1977, a warm, foggy Friday night at Fenway, Catfish Hunter had the worst outing of the worst season of his career.

All Jimmy Hunter needed was a nickname. Finley settled quickly on Catfish. He’d tell the press that Hunter had been missing one night and that his folks found him down by the stream with one catfish lying beside him and another on his pole. Hunter himself didn’t see what was wrong with “Jim,” but he wasn’t going to argue with the guy who was about to write him a check for seventy-five thousand dollars.

He estimated that he could put the ball within three inches of his catcher’s target 90 percent of the time; others figured his margin of error closer to one or two inches. The key to his control was his repetitive motion. “If you go out

to the mound after he’s pitched a game you’ll see three marks: one where he stands when he’s on the rubber, one where his left foot lands, one where his right foot lands,” his former teammate Doc Medich told J. Anthony Lukas for a 1975 New York Times Magazine profile. “Most players leave the mound all scratched up like a plowed cornfield.”

Hunter struggled in spring training in ’77, his fastball hovering in the low seventies.

Hunter made his June 17 start at Fenway, but he didn’t survive the first inning.

20.

THE fog cleared overnight. Saturday was sunny, hot, and humid. noon the narrow streets surrounding Boston’s cozy bally-ard were choked with people as the temperature climbed toward a hundred degrees.

“Uh-oh,” interrupted Messer’s longtime broadcast partner, Phil Rizzuto. “I’m sorry, Frank, but I think Billy’s calling Paul Blair to replace Jackson, and Jackson doesn’t know it yet. We’re liable to see a little display of temper here … It’s Reggie’s own fault really. On that ball he did not hustle.”

The Fenway crowd caught sight of Blair trotting across the field and let out a roar. Reggie, who was chatting with Fran Healy, his arms draped casually over the green fence of the bullpen, was practically the only guy in the ballpark with no idea what was going on. Healy told Reggie to turn around. Reggie glanced over his shoulder and saw Blair coming toward him. Reggie pointed at himself—You mean me?—in disbelief. Blair nodded. “What the hell is going on?” Reggie asked. Blair shrugged. “You’ve got to ask Billy that.” The NBC cameras followed Reggie off the field and into the dugout. Initially, he looked more puzzled than angry bounding down the dugout steps with his hands spread, palm side up, in an expression of utter confusion. Martin was waiting for him, neck cords bulging, knees bent, arms dangling impatiently at his side. “What the fuck do you think you’re doing out there?” he asked.

Martin started after Reggie. “There they go!” said Garagiola. Ray Negron quickly threw a towel over the lens of the dugout camera, only it was the camera in center field that was recording all the action.

“You don’t like me—you’ve never liked me,” Reggie yelled back at Martin as he made his way down the ramp. “I was livid,” Reggie recalled later, “but I wasn’t going to fight him in the dugout.” He was going to fight him in the locker room. Reggie stripped down to his undershirt and uniform pants, leaving his spikes on so he wouldn’t lose his footing on Fenway’s clubhouse carpeting, and waited for the game to end.

but Healy eventually persuaded Reggie to shower and leave the ballpark before the game ended. Negron came down to the clubhouse to check on Reggie and to ask if he needed a cab back to the hotel. Reggie wanted to walk.

A little later, Newsday’s Steve Jacobson called from the lobby to ask if he could come up. His deadline was approaching, and he didn’t want to file his copy without a quote from Reggie.

“Thank God I’m a Christian. Christ got my mind right. I won’t fight

the man. I’ll do whatever they tell me.” Before long, though, Reggie’s emotions had taken over. “It makes me cry, the way they treat me on this team. I’m a good ballplayer and a good Christian and I’ve got an IQ of 160, but I’m a nigger and I won’t be subservient. The Yankee pinstripes are Ruth and Gehrig and DiMaggio and Mantle. They’ve never had a nigger like me before.” The exception was Steinbrenner: “I love that man. He treats me like somebody. The rest of them treat me like dirt.” Reggie dropped down to his knees and began gesticulating wildly, the paranoid preacher who spied the devil’s shadows all around him. “He was talking about how everybody wanted a piece of him and was coming after him and how nobody understood him,” Pepe recalls. On and on he went as Torrez sat silent and the writers scribbled madly. “I’m going to play the best that I can for the rest of the year, help this team win, then get my ass out of here.”

21.

THE image that had been seared on the nation’s consciousness, courtesy of NBC Sports, was now plastered on sports pages across the country: the brawny black slugger, his glasses removed and set aside, standing chest to chest with his scrawny white manager.

Yet the race issue was not so easy to set aside, especially considering that this wasn’t Martin’s first clash with an outspoken black player. When he

arrived in Detroit in 1970, Martin had inherited the outfielder Elliott Maddox, a University of Michigan graduate and convert to Judaism whom Martin dumped as quickly as he could.

“Billy was a racist and an anti-Semite,” Maddox says now. “He had a drinking problem, and he had psychological problems stemming from his childhood.

For the most part, New York was proud of Martin—their working-class hero, their link to a better era—for standing up to the arrogant, overpaid slugger.

The dugout incident at Fenway proved to be something of a turning point for Reggie. Over the years he came to sound very different on the subject of race, speaking eloquently about how his own coming of age had traced the arc of the postwar emergence of his race: “I was colored until I was 14, a Negro until I was 21, and a black man ever since.” He spoke out, forcefully and persuasively, against baseball’s failure to integrate at the executive and managerial level.

22.

Even before he’d had to be restrained from attacking his right fielder on national television, Martin was having problems. His heavily favored team was struggling to stay in the pennant race.

Since the start of the season Steinbrenner had been calling him on a nearly daily basis to share his unsolicited opinion that Reggie Jackson should be batting cleanup, which of course only strengthened Martin’s resolve to hit him fifth or sixth.

There was no reason to expect Martin was going to survive the Fenway crisis. He had met with Reggie and Gabe Paul, the unofficial liaison between Steinbrenner and Martin, first thing in the morning and it had not gone well. Martin’s first mistake was referring to Reggie as “boy,” which an even more sensitive than usual Reggie interpreted as a racial slur. Martin insisted that it was just an expression, but Reggie was not inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt.

23.

IT wasn’t all bad being Reggie Jackson in the summer of 1977; if nothing else, he’d made a new friend, Ralph Destino.

Destino, the chairman of Cartier, was living in a swanky penthouse on Seventy-ninth and Park Avenue, just a couple of blocks away from Reggie.

the Stork carried New York from the dark days of the Depression through its postwar optimism, Maxwell’s, with its stained glass kaleidoscope ceiling, Tiffany lamps, and human buffet of bachelors and bachelorettes, arrived just in time to spirit the city through the swinging sixties and sordid seventies.

Reggie and Destino tried Maxwell’s a couple of times, but once they had to wait for a table they vowed never to return. It was just as well. Maxwell’s may have had swinging singles, but McMullen’s had models.

Rudy Giuliani (then a young prosecutor), Donald Trump, and Cheryl Tiegs all were fixtures at McMullen’s, as was Steinbrenner, but Reggie was the only ballplayer who ate there. “I used to get mostly professional tennis players—Rod Laver, Bjorn Borg, Chris Evert, John McEnroe, Vitas Gerulaitis,” recalls McMullen. “It really was more of a hangout for tennis players. Baseball players tend not to be very sophisticated.”

By 1 a.m. twenty black limousines would be lined up out front on Third Avenue, waiting to transport revelers seamlessly to their next nocturnal playpen, Studio 54.

“We went to Studio 54 like it was part of the evening,” says Destino. “It was so hot then that there would always be a throng on the sidewalk begging, trying to get in, doing anything that they possibly could. But Reggie would walk through that crowd like Moses through the river. The sea would part.”

Reggie was starting to dread the game he loved. He was waking up in the middle of the night and wandering out to his balcony twenty stories above Fifth Avenue, where he’d stare out at the New York City skyline and wonder how he was going to make it through the summer.

What upset him was his failure to understand why. ‘Why are they doing this to me?’”

24.

“NOW is the summer of our discotheques,” wrote night-crawling journalist Anthony Haden-Guest in New York magazine in June 1977. “And every night is party night.”

Studio 54, the discotheque that defined an entire era of nightlife, had opened two months earlier, and Paramount Pictures had just begun filming Saturday Night Fever.

Like any fad that seems to erupt into the national consciousness, this one had been percolating below ground for years: in gay hot spots along the abandoned West Side waterfront, in the vacant sweatshops south of Houston Street, in the dingy recreation rooms of Bronx and Brooklyn housing projects, in the empty ballrooms of aging midtown hotels. If New York’s disco scene had a party zero, it was David Mancuso’s Love Saves the Day bash on Valentine’s Day 1970.

“The whole scene was a response to the sixties,” says Michael Gomes, an early disco devotee who moved to New York from Toronto in 1973. “Instead of changing the world, we wanted to create our own little world.”

The Bronx’s own fledgling dance culture, one that eventually blossomed into hip-hop, was simultaneously gestating. It was less formal than the new wave of discotheques; a DJ might set up his table in a playground, run extension cords into the nearest lamppost, and start playing.

None of the hard-core dance clubs sold alcohol, but there were always plenty of drugs, chiefly acid, amyl nitrate, pot, mescalin, coke, Quaaludes (also known as disco biscuits), and speed.

Carmen d’Alessio

Since coming to New York in 1965, the Peruvian-born d‘Alessio had worked as a translator for the United Nations and logged a stint in public relations for Yves Saint Laurent, but in more recent years she had discovered her true calling, party planning. When Rubell and Schrager first spotted her in the winter of ’76, she was wearing a bikini and dancing on the shoulders of a tall black male model at a Brazilian Carnival theme party she’d organized.

Rubell and Schrager persuaded d‘Alessio to come work for them.

In addition to any celebrity whose address she could beg, borrow, or steal, d’Alessio sent invitations to everyone on the mailing list of the Ford Modeling Agency, Andy Warhol’s Factory, and the Islanders, a group of several thousand gay men who summered on Fire Island. Come opening night, the place was mobbed. “My mother had to be carried in over the crowd,” d’Alessio recalls. Studio 54 took the escapist ethic of the disco scene to its absurd extreme. An

this wasn’t about avoiding reality as much as it was about obliterating it.

“I don’t know if I was in heaven or hell,” Lillian Carter, mother of President Jimmy, reflected on her first visit there. “But it was wonderful.”

New York’s disco DJs were playing to bigger crowds than ever before, yet paradoxically, their power was slipping. Radio stations were now catching on to disco, so the record companies no longer needed to cultivate club DJs.

all the new clubs served booze, which made the dancing sloppy. Michael Gomes, who was now publishing a newsletter for DJs called Mixmaster, referred derisively to the drunk and stoned dancers at Studio 54 as “discodroids.”

If disco music was euphoric, hypnotic, punk rock was assaultive, relentless; if discos like Studio 54 provided an escape from the ugliness of New York, its punk analog, a urine-stained dive on the Bowery called CBGB, embraced and indulged it.

Other protopunk acts including Blondie, Patti Smith, and the Ramones, soon followed. At a time when rock ‘n’ roll connoted suburban stadiums, a rock scene was born on, of all places, the Bowery. “Broken youth stumbling into the home of broken age,” wrote Frank Rose, noting the irony in The Village Voice in the summer of ’76.

The Talking Heads, another one of the most popular bands at CBGB, wasn’t doing much better. Their 1977 album, Talking Heads ’77, barely broke 100. Touring the country that summer in the wake of its release, the band found itself playing mostly at pizza parlors.

25.

WITH Bella Abzug and Mario Cuomo now in the race, David Garth adjusted the odds for his candidate, Ed Koch, from twenty to one to forty to one.

Reflecting on the ’77 campaign years later, Garth opted for a different metaphor: “Koch … was never the flashy guy who went out for the long pass. He was the Bronko Nagurski of politics, three yards and a cloud of dust.”

Not only was Koch funny-looking and not especially charming, but he lived in Greenwich Village, had no girlfriend, and had never been married.

Garth’s plan was to keep the focus on the issues, to somehow make a virtue of his candidate’s lack of charm. Koch was unknown, but at least he wasn’t disliked. It was no secret that New York was on the ropes. For the purposes of political narrative anyway, it was easy to put the starry-eyed Lindsay and the special interest–beholden Beame as the one-two punch that landed it there. The result was the made-for-TV tagline: “After eight years of charisma and four years of the clubhouse, why not try competence?”

26.

IN the early summer of 1977, as the mayoral candidates started jockeying in earnest to present themselves as the answer to the city’s problems, New Yorkers were already creatively exploiting the very neglect that the politicians were decrying. Just as the gay community had colonized the abandoned West Side piers and graffiti writers were transforming unguarded subway cars into art installations, painters, sculptors, and entrepreneurs were repurposing empty factories and sweatshops in the area below Houston Street.

Rockefeller, the head of the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association, envisioned SoHo as a gateway to Wall Street, complete with office buildings, luxury apartment towers, even a sports stadium.

The derelict lofts of SoHo were also becoming popular among avant-garde jazz musicians

a formidable antiexpressway lobby was materializing, led by author–cum–neighborhood superheroine Jane Jacobs and a loose-knit coalition of Greenwich Village activists that included an ambitious young politician named Ed Koch, all of whom considered the expressway a threat to an indigenous New York neighborhood.

in 1969 the expressway plan was finally scotched.

To a city already casting about for ways to shore up its eroding tax base, SoHo’s artistic community was looking more and more like an economic boon.

the neighborhood was officially declared a landmark district, ensuring that it would forever remain out of harm’s way.

For years people had been calling SoHo the new Montparnasse. The twenty-six-hundred-square-foot Dean & DeLuca would be its fromagerie, patisserie, and boulangerie all rolled into one.

In later years the proud pioneers who had settled—or resettled anyway—this urban frontier would point darkly to the day, identifying it as the tipping point, the moment when their beloved neighborhood made the irreversible transition from scruffy artists’ colony to theme park for the taste-fetishizing upwardly mobile.

these buildings that had once stood as ghostly reminders of the disappearance of manufacturing from New York were now being transformed into monuments to the city’s resilience, powerfully evoking the past even as they hinted at a postindustrial future.

PART TWO

27.

WILLIAM Jurith left for work in the early afternoon of Wednesday, July 13. He was supposed to have the day off, but when a colleague told him that he needed to take care of some personal business, Jurith, who was putting his son through law school, volunteered to pick up his colleague’s four-to-midnight shift.

Jurith was a system operator for Consolidated Edison. He had no training as an engineer,

the company served all five boroughs and most of Westchester County, a total of nine million people.

The city’s stringent clean-air regulations made it prohibitively expensive to depend on local generators that were required to burn costly low-sulfur oil rather than cheaper alternatives like coal. So Con Ed built plants outside the city and bought power from neighboring states rather than make it. Most of that power came from the north—from

Power failures, or at least the fear of them, had been a rite of summer in New York since 1965.

The system’s first major test of ’77 was now on its way. A blanket of hot, muggy weather was descending on the city like a giant steam iron.

Unlike gas, electricity can’t be stored; it has to be used as it is generated. So as a day got hotter, the system operator had to anticipate the growing demand for power and find the most efficient ways to meet it. That meant bringing up generation with the help of gas turbines and special reserve generators known as peaking units, as well as contracting to buy additional power on the spot market. On July 13 demand peaked at 7,264 megawatts at 4 p.m.,

At 8:37 p.m., Jurith looked up

Two circuit breakers had tripped in Westchester County, and a pair of high-voltage transmission lines had opened.

A horn blared. Jurith glanced at the mimic board. A needle was falling like the pressure gauge on a deflating tire—nine hundred megawatts, eight hundred megawatts, seven hundred megawatts—all the way to zero. It was Indian Point, his “nukie.”

Either the mimic board was malfunctioning, or something was very, very wrong. Jurith punched a button on his communication console and was patched right through to Westchester’s district operator. “Yeah, Bill,” Westchester confirmed, “it looks like we lost the entire south bus [Buchanan], including Unit 3 [Indian Point] … The station operator tells me he saw lightning.”

The breakers were supposed to open the affected lines and isolate the problem until the fault dissipated. The fault did dissipate in less than a second, but the circuit breakers never reclosed to allow the flow of power to resume.

with three transmission lines out of service, the remaining lines were going to be shouldering a much bigger energy burden than they were built to handle.

At 8:40 p.m. a high-pitched alarm sounded on Jurith’s desktop monitor. A key feeder connecting the Con Ed system to New England was exceeding its limit by a hundred megawatts. If the line wasn’t deloaded right away, it was going to fry.

28.

Studying the big board, Kennedy could see no alternative. Con Ed was going to have to unplug some customers. He called Jurith.

At 8:59 Kennedy called him again. This time he was a little more insistent: “Bill, I hate to bother you, but you better shed about 400 megawatts of load or you’re going to lose everything down there.” “I’m trying to,” Jurith answered. “You’re trying to?” Kennedy asked incredulously. “All you have to do is hit the button to shed it and then we’ll worry about it afterwards—but you got to do something …” “Yeah, right,” Jurith answered. “Yeah, fine.” Jurith still refused to activate the load-shedding panel. He may have resented the fact that Kennedy, who wasn’t really his boss, was telling him what to do. He may have been clinging desperately to the hope that those three last feeders could support the system long enough for another solution to emerge. Probably he just couldn’t bring himself to pull the trigger. Jurith’s job was to keep people’s lights on, not to shut them off. “We got the impression that he was disintegrating,” recalls Carolyn Brancato,

At 9:08, Jurith’s boss, Charles Durkin, called in.

Jurith didn’t notify Durkin that the power pool had been urging him to shed load for more than ten minutes. Instead, he told Durkin about his plans for Feeder 80. “Where’s the power going to go if you cut it out?” Durkin replied. “You can’t cut it out.” While Jurith was on the phone with Durkin, Kennedy called again on the green phone, a special dedicated hotline for emergency use only. Jurith’s deputy, John Cockerham, answered. “Tell Bill to go into voltage reduction immediately down there,”

At 9:19, Feeder 80 drooped into a tree. Circuit breakers were tripped, and the line opened. Con Ed had lost its only connection to the north.

Kennedy made his final call to the Con Ed control room at 9:27. Cockerham picked up. “I’m going to tell you one more time …”

No more than thirty megawatts were shed. Something had obviously gone wrong. In all likelihood, Jurith failed to operate the load-dumping equipment properly.

The Con Ed system was now officially islanded, cut off from all external power sources. It shifted much of its load to its biggest in-city generator, Big Allis, a thousand-megawatt steam unit in Queens. Like a circular saw fighting a losing battle with an oversize piece of wood, Big Allis’s turbines ground to a halt.

Seconds later the generator automatically shut itself down. The city’s nine remaining generators buckled instantaneously under the increased load.

Ten thousand traffic lights blinked off. Subway trains froze between stations. Elevators, water pumps, air conditioners—everything sputtered to a halt. All five boroughs and most of Westchester County were suddenly without power.

29.

OFFICER Wilton Sekzer, a broad, mustachioed man, about five feet ten, with jowly cheeks and rheumy hazel eyes, was in the living room of his apartment in Sunnyside, Queens, when the lights went out. On the way into the kitchen to check his fuse box, he peeked out the window. The whole block was dark. Sekzer ran up three flights and swung open the metal door to his roof. The whole neighborhood was dark.

Sekzer had been sent to the Eighty-third Precinct from Emergency Services in the summer of ’75, when the city’s fiscal crisis forced the Police Department to lay off five thousand officers.

Down five thousand men at a time of soaring crime, the city’s depleted precincts were going to need all the beat cops the department could muster.

The Eighty-third Precinct was not exactly a desirable assignment in 1977. The prior year it had confronted more criminal activity than any other precinct in central Brooklyn. Many truck drivers insisted on police escorts when making deliveries in the neighborhood.

It didn’t help that the fiscal crisis had virtually eliminated Police Department support staff. It took anywhere from ten to fourteen hours for a cop to process a single perp.

Rookies were taught a few important lessons when they reported for duty at the Eight-Three. Don’t walk too close to the buildings (someone might drop a brick on you). Don’t let neighborhood kids wear your hat (lice). Always check the earpiece on call boxes before using it (dog shit).

30.

nothing could have prepared them for what greeted them on Broadway. Thousands of people were already out on the street; thousands more were pouring in from every direction. “If they had turned on the lights,” one cop remembers, “it would have looked like the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.”

According to one police report, the looting had started at 9:40 p.m., only minutes after the onset of darkness. Marauding bands were sawing open padlocks. They were taking crowbars to steel shutters, prying them open like tennis-ball-can tops or simply jimmying them up with hydraulic jacks

The most expensive shops were hit first: jewelry, electronics, and furniture stores. A teenager attached a chain to the bumper of a stolen truck and tore off the gates of a luxury item shop called Time Credit. He pitched a garbage pail through the window and filled the truck with TVs, air conditioners, and a rack of watches.

For the cops, there was no time for paperwork. All the stolen merchandise was piled up in the property room in the back of the station house. Polaroids were snapped of the cop with his perp. Time and place of arrest were scribbled on the backs. The prisoner was stuffed into a holding cell, and the arresting officer headed back out into the mayhem.

Bullets, as well as bricks and bottles, were raining down from rooftops.

For some reason, though, the Eight-Three received no backup from any of the city’s quieter precincts.

31.

MAYOR Beame had just started in on a campaign reelection speech to a standing room only crowd of five hundred at the Traditional Synagogue in Co-op City when the lights went out.

The mayor climbed into his Chrysler and was spirited down to Gracie Mansion, where a candlelight strategy session was already in progress.

When he returned to police headquarters at a little after 5 a.m., Beame held another press conference in which he called on religious leaders to get into patrol cars and calm their communities. One of those who did, a priest in the Bronx, had his altar stolen while he was gone.

Police Commissioner Codd had ordered all officers to report for duty immediately, only instead of insisting that everyone try to find a way to get to his command, Codd told them to report to the nearest precincts.

This proved to be an enormous mistake. Ever since the 1962 repeal of the Lyons Law, which had required all cops to live in the city, police officers had been moving to the

suburbs in droves. Most of those who continued to reside in the city lived in Queens or on Staten Island, so in the early hours of the blackout, there were hundreds, maybe thousands, of idle cops hanging around quiet precincts.

Morale in the department had been on the skids ever since the ’75 layoffs.

as the looting peaked between midnight and 4 a.m., some ten thousand cops, 40 percent of the force who were neither on vacation nor on sick leave, had yet to check in.

32.

THE looting was by no means citywide. In some of the tonier areas of Manhattan, restaurants moved tables outside to escape the heat. Several stretches of First Avenue on the Upper East Side might have been mistaken for streets in Paris, were it not for the angled cars, headlights on, that made it possible for diners to identify what they were eating.

To this day the blackout looting of 1977 remains the only civil disturbance in the history of New York City to encompass all five boroughs simultaneously.

The Bronx was hit even harder than Manhattan. By 11 p.m., the showroom windows of a Pontiac dealership on Jerome Avenue had been smashed, and fifty of the fifty-five new cars parked inside driven off into the black night.

473 stores in the Bronx were damaged; 961 looters were arrested.

Still, the character of the chaos in Bushwick was unique. “The crowds on Broadway in Bushwick seemed to possess a special kind of hysteria as the evening wore on,”

It was a spirit born of the poverty and desperation of ghetto life. Yet what was so remarkable about Bushwick was that it had been a sturdy middle-class enclave just a decade earlier. The speed of its decline was dizzying.

33.

IN Bushwick the arrests peaked at about 1:30 a.m. By then there were two shifts’ worth of cops—4 p.m. to midnight and midnight to 8 a.m.—out on the streets.

“You just wanted to stop the riot, so you beat up the looters with ax handles and nightsticks,” recalls Robert Knightly, a bearded, mild-mannered veteran of the Eight-Three who is now a defense attorney for Legal Aid.

34.

More than twenty fires were still burning along Broadway come Thursday morning, ten hours after the blackout had begun. The stifling heat was made more oppressive by the blanket of black smoke that hung heavy over the neighborhood.

“what was most upsetting was that you worked in this precinct. You worked with these people, you had taken care of them, and yet here they were, burning their own stores down.

35.

BROADWAY separates Bushwick from Bedford-Stuyvesant, which was once a middle-class enclave too, a neighborhood of stickball, brownstones, and postwar optimism. As the fifties wore on, though, more and more of Bed-Stuy’s working-class white families migrated to the suburbs.

In 1965 the Department of Housing and Urban Development called Bed-Stuy “the heart of the largest ghetto in America.”

Bushwick was less dependent on the dying navy yard for jobs than much of the borough.

Some of Bushwick’s working class pulled up stakes, in most cases pushing east into Long Island. Others dug in their heels.

Even those all too aware of Bushwick’s woes couldn’t have predicted what was coming next. When a house near St. Martin’s burned down in 1969, neighbors expressed their condolences to the owner. Nobody thought arson. “We felt sorry for him,” says St. Martin. “Insurance or no insurance, you didn’t burn your own house down and put other people at risk. It was unthinkable. It just didn’t happen.”

1972, Bushwick’s two ladder companies, 124 and 112, went on more then six thousand runs, the unofficial benchmark of a severe social crisis.

The fires were set by landlords who were tired of trying to evict delinquent tenants.

They were set by vandals who intended to return for the plumbing systems, which were easier to extract and sell once the firemen had knocked down the walls. They were set by idle kids who wandered the streets aimlessly after school.

Most of Bushwick’s buildings had been built for German immigrants before 1910. More than half of them were made of wood and designed with air shafts over their stairwells. They burned like furnaces.

As Jim Sleeper wrote in The Closest of Strangers, his trenchant 1990 book about liberalism and race in New York, “By the mid-1970s, Bushwick was … a prison of traumatized welfare recipients reeling in rage and despair.” In the darkness of July 13, 1977, that rage and despair found an outlet.

36.

IN the days after the blackout a damp, acrid smell permeated Bushwick. Fire-damaged buildings sloughed off large chunks of debris. Broken pipes burped brown water onto sidewalks. In the litter-strewn streets, people filled shopping carts with abandoned packages of meat.