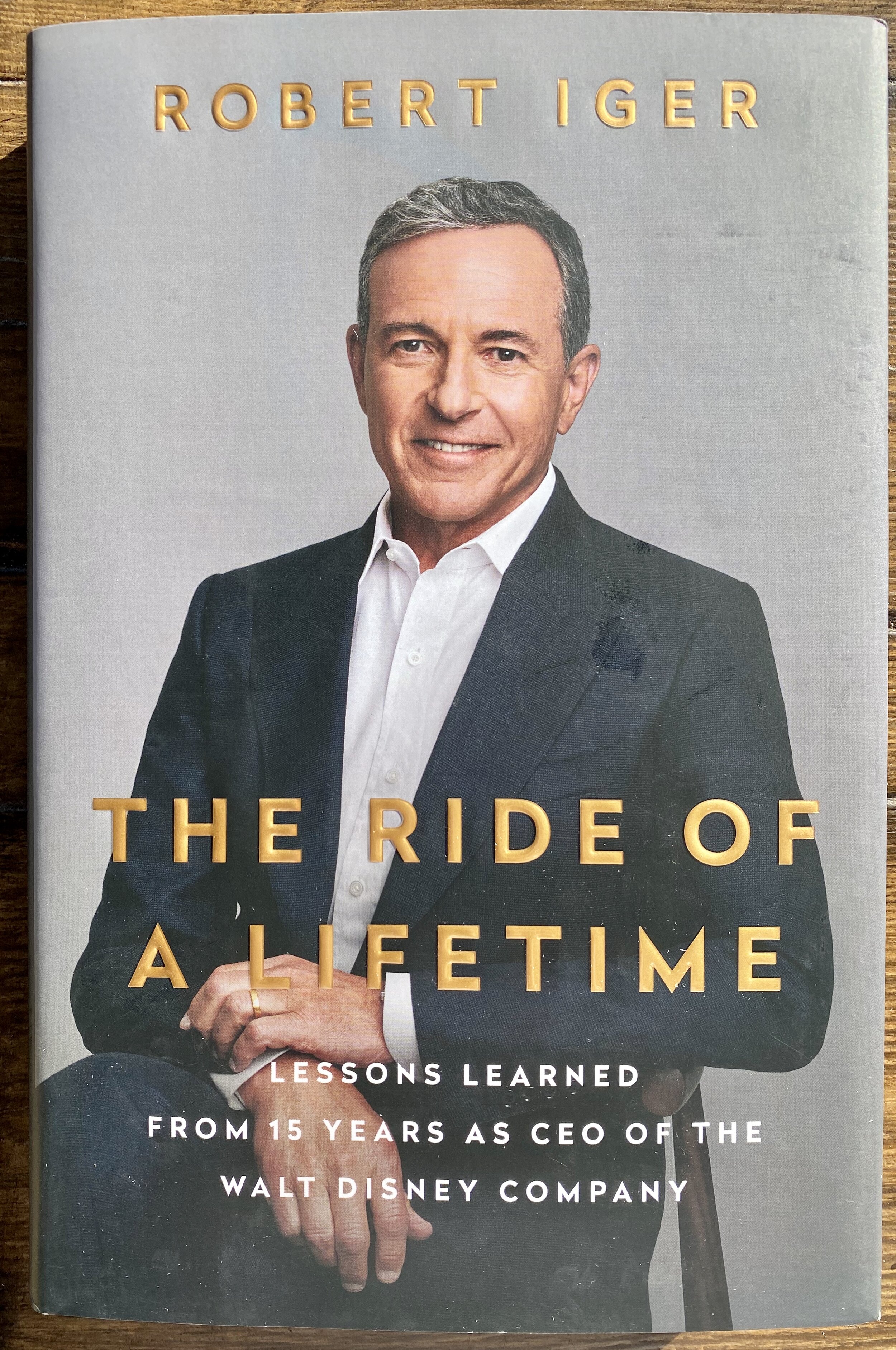

Book Summary: The Ride of a Lifetime by Bob Iger

CEO autobiographies are often stuffy. They tilt toward self-grandeur, empty platitudes, and stiff writing.

Many of these books are popular only because people want to signal they’ve read them.

So I was surprised how much I liked The Ride of a Lifetime, Iger’s recounting of his life and career, from his beginnings as a studio supervisor at ABC up to his reign as CEO at Disney, which continues today.

The tone and writing are accessible—not pretentious—which in line with Iger’s personal brand and leadership style.

In the book, Iger:

Shares valuable lessons on leading from humility

Offers insight on the difficulty, strategy, and importance of taking big risks

Provides interesting details on the personalities and strategies involved in acquiring and integrating Pixar, Marvel, and Star Wars

One lesson that runs through the entire book: all business is personal.

Realizing this truth and addressing it makes taking big risks easier—and reduces the chances of those risks going badly.

What follows are my Kindle highlights from the book: the passages I found to be the most interesting, useful, and surprising.

And I mix in some commentary. (No extra charge.)

Part One: Learning

Chapter 1: Starting at the Bottom

In this chapter, Iger talks about the early days of his career, and what he learned from his mentors, including ABC Sports and News legend Roone Arlidge.

His [Arlidge’s] mantra was simple: “Do what you need to do to make it better.” Of all the things I learned from Roone, this is what shaped me the most.

On the pursuit of perfection—and not being paralyzed by it:

Jiro Ono, whose restaurant has three Michelin stars and is one of the most sought-after reservations in the world.

He is described by some as being the living embodiment of the Japanese word shokunin, which is “the endless pursuit of perfection for some greater good.”

It’s a delicate thing, finding the balance between demanding that your people perform and not instilling a fear of failure in them.

In your work, in your life, you’ll be more respected and trusted by the people around you if you honestly own up to your mistakes.

For all of his immense talent and success, Roone was insecure at heart, and the way he defended against his own insecurity was to foster it in the people around him.

Chapter 2: Betting on Talent

Chapter two covers ABC’s acquisition by Cap Cities and lessons learned from the executives who lead the company.

… it was also a function of the culture that Tom and Dan created. They were two of the most authentic people I’ve ever met, genuinely themselves at all times. No airs, no big egos that needed to be managed, no false sincerity. They comported themselves with the same honesty and forthrightness no matter who they were talking to. They were shrewd businesspeople (Warren Buffett later called them “probably the greatest two-person combination in management that the world has ever seen or maybe ever will see”), but it was more than that. I learned from them that genuine decency and professional competitiveness weren’t mutually exclusive. In fact, true integrity—a sense of knowing who you are and being guided by your own clear sense of right and wrong—is a kind of secret weapon. They trusted in their own instincts, they treated people with respect, and over time the company came to represent the values they lived by.”

Iger on Roone Arlidge’s storytelling instincts:

We were scheduled to air a three-hour Olympics preview the night before the opening ceremonies, and for weeks I’d been trying to get Roone to focus on it. He finally watched it after arriving in Calgary, the night before it was scheduled to air. “It’s all wrong,” he said. “There’s no excitement. No tension.” A team of people worked through the night to execute all of his changes in time to get it on the air. He was right, of course.

When warm weather wreaked havoc on the Calgary Olympics, causing numerous event cancellations, Iger recalls his mindset:

Things were dire, for sure, but I needed to look at the situation not as a catastrophe but as a puzzle we needed to solve, and to communicate to our team that we were talented and nimble enough to solve these problems and make something wonderful on the fly.

Chapter 3: Know What You Don’t Know (and Trust in What You Do)

Chapter three focuses on working with creative people—guiding them to get the best from them without destroying their initiative and creative drive.

True authority and true leadership come from knowing who you are and not pretending to be anything else.

When I am asked to provide insights and offer critiques, I’m exceedingly mindful of how much the creators have poured themselves into the project and how much is at stake for them.

I never start out negatively, and unless we’re in the late stages of a production, I never start small. I’ve found that often people will focus on little details as a way of masking a lack of any clear, coherent, big thoughts.

The first time I sat down with Ryan Coogler to give him notes on Black Panther, I could see how visibly anxious he was. He’d never made a film as big as Black Panther, with a massive budget and so much pressure on it to do well. I took pains to say very clearly, “You’ve created a very special film. I have some specific notes, but before I give them to you, I want you to know we have tremendous faith in you.”

Empathy is a prerequisite to the sound management of creativity, and respect is critical.

Of all the lessons I learned in that first year running prime time, the need to be comfortable with failure was the most profound. Not with lack of effort but with the unavoidable truth that if you want innovation—and you should, always—you need to give permission to fail.

Chapter 4: Enter Disney

Chapter four covers Disney’s acquisition of Cap Cities / ABC, and Iger’s move into a larger role, with the challenges of assimilating ABC into a new corporate culture.

Iger discusses the challenge of facing difficult situations head-on, and the fact that Michael Ovitz and Michael Eisner should have known their working relationship would not succeed:

They should both have known that it couldn’t work, but they willfully avoided asking the hard questions because each was somewhat blinded by his own needs.It’s a hard thing to do, especially in the moment, but those instances in which you find yourself hoping that something will work without being able to convincingly explain to yourself how it will work—that’s when a little bell should go off, and you should walk yourself through some clarifying questions. What’s the problem I need to solve? Does this solution make sense? If I’m feeling some doubt, why? Am I doing this for sound reasons or am I motivated by something personal?

On Michael Ovitz’s time management:

Managing your own time and respecting others’ time is one of the most vital things to do as a manager, and he was horrendous at it.”

Chapter 5: Second in Line

Chapter Five covers Iger’s years running ABC under Eisner, as he hoped to ascend to the COO role at Disney.

… good leadership isn’t about being indispensable; it’s about helping others be prepared to possibly step into your shoes—giving them access to your own decision making, identifying the skills they need to develop and helping them improve, and, as I’ve had to do, sometimes being honest with them about why they’re not ready for the next step up.

On motivating Roone Arlidge to create a strong 24-hour ABC News special as the calendar rolled to the year 2000:

It could be impossible to execute, but when has that ever stopped you?

Chapter 6: Good Things Can Happen

This chapter focuses on Disney’s growth while Iger served as chief operating officer under Michael Eisner, as an increasingly hostile board and economic environment robbed Eisner of his power and optimism.

Michael’s biggest stroke of genius, though, might have been his recognition that Disney was sitting on tremendously valuable assets that they hadn’t yet leveraged.

These assets include:

One was the popularity of the parks. If they raised ticket prices even slightly, they would raise revenue significantly … building new hotels at Walt Disney World [and] expansion of theme parks.

Even more promising was the trove of intellectual property—all of those great classic Disney movies—just sitting there waiting to be monetized. They began selling videocassettes of the classic Disney library to parents who’d seen them in the theater when they were young and now could play them at home for their kids. It became a billion-dollar business.

… the Cap Cities/ ABC acquisition in 1995, which gave Disney a big television network, but, most important, brought in ESPN

On Eisner’s leadership style:

What struck me, and what was invaluable in my own education, was his ability to see the big picture as well as the granular details at the same time, and consider how one affected the other.

For his part, he’d say, “Micromanaging is underrated.”

On courage and optimism in leadership:

Of great interest to me was the fact that almost every traditional media company, while trying to figure out its place in this changing world, was operating out of fear rather than courage, stubbornly trying to build a bulwark to protect old models that couldn’t possibly survive the sea change that was under way.

...optimism in a leader, especially in challenging times, is so vital. Pessimism leads to paranoia, which leads to defensiveness, which leads to risk aversion.

Optimism sets a different machine in motion. Especially in difficult moments, the people you lead need to feel confident in your ability to focus on what matters, and not to operate from a place of defensiveness and self-preservation.

This isn’t about saying things are good when they’re not, and it’s not about conveying some innate faith that “things will work out.” It’s about believing you and the people around you can steer toward the best outcome, and not communicating the feeling that all is lost if things don’t break your way. The tone you set as a leader has an enormous effect on the people around you.

Chapter 7: It’s About The Future

This chapter covers Iger’s battle to become CEO following Eisner’s removal.

THE CHALLENGE FOR me was: How do I convince the Disney board that I was the change they were looking for without criticizing Michael in the process?

Iger spoke to the Disney board, imploring them not to focus on the past issues of the company, but to look to his plan for the future:

“You cannot win on the defensive. It’s only about the future. It’s not about the past.” That may seem obvious, but it came as a revelation to me. I didn’t have to rehash the past. I didn’t have to defend Michael’s decisions. I didn’t have to criticize him for my own benefit. It’s only about the future. Every time a question came up about what had gone wrong at Disney over the past years, what mistakes Michael made, and why they should think I’m any different, my response could simply and honestly be: “I can’t do anything about the past. We can talk about lessons learned, and we can make sure we apply those lessons going forward. But we don’t get any do-overs. You want to know where I’m going to take this company, not where it’s been. Here’s my plan.”

After being named CEO, Iger reflected on shaping culture and setting priorities:

A company’s culture is shaped by a lot of things, but this is one of the most important—you have to convey your priorities clearly and repeatedly.

You can do a lot for the morale of the people around you (and therefore the people around them) just by taking the guesswork out of their day-to-day life.

… this kind of messaging is fairly simple: This is where we want to be. This is how we’re going to get there. Once those things are laid out simply, so many decisions become easier to make, and the overall anxiety of an entire organization is lowered.

After the meeting with Scott, I quickly landed on three clear strategic priorities. They have guided the company since the moment I was named CEO:

1) We needed to devote most of our time and capital to the creation of high-quality branded content.

2) We needed to embrace technology to the fullest extent, first by using it to enable the creation of higher quality products, and then to reach more consumers in more modern, more relevant ways.

3) We needed to become a truly global company.

Part Two: Leading

Chapter 8: The Power of Respect

Chapter eight discusses Iger’s transition to Disney CEO and the initial challenges he faced: repairing relationships with the board (particularly Roy Disney, who had been campaigning in the press against the company’s direction), repairing the relationship with Pixar and Steve Jobs, and laying the groundwork to transform Disney’s structure and culture.

The truth was, it wasn’t just Michael who was at odds with Roy [Disney]; besides Stanley, not enough people within Disney had given him the respect he felt he deserved, including his long-gone uncle, Walt. I had never had any real connection to Roy, but I detected vulnerability in him now. There was nothing to be gained by making him feel smaller or insulted. He was just someone looking for respect, and getting it had never been especially easy for him. It was so personal, and involved so much pride and ego, and this battle of his had been going on for decades.

All business is personal:

The drama with Roy reinforced something that tends not to get enough attention when people talk about succeeding in business, which is: Don’t let your ego get in the way of making the best possible decision.

If you approach and engage people with respect and empathy, the seemingly impossible can become real.

Chapter 9: Disney-Pixar and a New Path to the Future

In Chapter nine, Iger discusses his growing relationship with Steve Jobs, and the difficult path to acquiring Pixar to transform Disney’s animation group.

THOSE MONTHS SPENT talking with Steve about putting our TV shows on his new iPod began—slowly, tentatively—to open up into discussions of a possible new Disney/ Pixar deal.

“The average tenure for a Fortune 500 CEO is less than four years.” At the time, it was a joke between us [Iger and his wife Willow Bay], to make sure the expectations I set for myself were realistic. Now, though, she said it with a tone that implied I had little to lose by acting fast. “Be bold,” was the essence of her advice.

This was about a week and a half before our announcement about the video iPod, so we spent a couple of minutes talking about that before I said, “Hey, I have another crazy idea. Can I come see you in a day or two to discuss it?” I didn’t yet fully appreciate just how much Steve liked radical ideas. “Tell me now,” he said.

Sometimes opportunity strikes before you are prepared. And you just have to go for it:

While still on the phone, I pulled into my driveway. It was a warm October evening, and I turned the engine off, and the combination of heat and nerves caused me to break out in a sweat. I reminded myself of Willow’s advice—be bold. Steve would likely say no immediately.

“What do you think about the idea of Disney buying Pixar?” I waited for him to hang up or to erupt in laughter.

Instead, he said, “You know, that’s not the craziest idea in the world.”

PEOPLE SOMETIMES SHY AWAY from taking big swings because they assess the odds and build a case against trying something before they even take the first step. One of the things I’ve always instinctively felt—and something that was greatly reinforced working for people like Roone and Michael—is that long shots aren’t usually as long as they seem.

A couple of weeks after that call in my driveway, he [Steve Jobs] and I met in Apple’s boardroom in Cupertino, California.

He stood with marker in hand and scrawled PROS on one side and CONS on the other. “You start,” he said. “Got any pros?” I was too nervous to launch in, so I ceded the first serve to him. “Okay,” he said. “Well, I’ve got some cons.” He wrote the first with gusto: “Disney’s culture will destroy Pixar!”

“Fixing Disney Animation will take too long and will burn John and Ed out in the process.” “There’s too much ill will and the healing will take years.” “Wall Street will hate it.” “Your board will never let you do it.”

“Pixar will reject Disney as an owner, as a body rejects a donated organ.” There were many more, but one in all cap letters, “DISTRACTION WILL KILL PIXAR’S CREATIVITY.”

… we moved to the pros. I went first and said, “Disney will be saved by Pixar and we’ll all live happily ever after.” Steve smiled but didn’t write it down. “What do you mean?” I said, “Turning Animation around will totally change the perception of Disney and shift our fortunes. Plus, John and Ed will have a much larger canvas to paint on.”

“A few solid pros are more powerful than dozens of cons,” Steve said.

Steve was great at weighing all sides of an issue and not allowing negatives to drown out positives, particularly for things he wanted to accomplish. It was a powerful quality of his.

I was told over and over that it was too risky and ill-advised. Many people thought Steve would be impossible to deal with and would try to run the company. I was also told that a brand-new CEO shouldn’t be trying to make huge acquisitions. I was “crazy,” as one of our investment bankers put it, because the numbers would never work out and this was an impossible “sale” to the street.

On taking risks:

Nothing is a sure thing, but you need at the very least to be willing to take big risks. You can’t have big wins without them.

On what’s really important in an acquisition:

A lot of companies acquire others without much sensitivity regarding what they’re really buying. They think they’re getting physical assets or manufacturing assets or intellectual property (in some industries, that’s more true than in others). In most cases, what they’re really acquiring is people. In a creative business, that’s where the value truly lies.

Iger recalls his mindset when addressing the Pixar acquisition with his board:

I entered the boardroom on a mission. I even took a moment before I walked into the room to look again at Theodore Roosevelt’s “The Man in the Arena” speech, which has long been an inspiration: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood.”

Jobs reveals his health issues just before the Pixar public announcement, jeopardizing the acquisition. Last-minute surprises can jeopardize a business deal, even after you think it’s sealed:

Just after noon, Steve found me and pulled me aside. “Let’s take a walk,”

He asked me for complete confidentiality, and then he told me that his cancer had returned.

“Steve, why are you telling me this?” I asked. “And why are you telling me now?” “I am about to become your biggest shareholder and a member of your board,” he said. “And I think I owe you the right, given this knowledge, to back out of the deal.” I checked my watch again. It was 12: 30, only thirty minutes before we were to announce the deal.

Chapter 10: Marvel and Massive Risks that Make Perfect Sense

In Chapter ten, Iger discusses the challenges of acquiring Marvel: the CEO’s personality, the character licensing complexities, the skeptics of the deal, and overcoming stale cultural assumptions to create massive movie hits.

On the complexities of acquiring Marvel given its IP licensing deals:

Marvel was already contractually bound to other studios. They had a distribution agreement with Paramount for multiple upcoming films. They’d sold the Spider-Man rights to Columbia Pictures (which eventually became Sony). The Incredible Hulk was controlled by Universal. X-Men and The Fantastic Four belonged to Fox. So even if we could acquire everything that wasn’t tied up by other studios, it wasn’t as pure an IP acquisition as we would ideally have liked.

Your negotiating style has to be adaptable to the person you are negotiating with.

[Marvel CEO] Ike [Perlmutter] would never fit easily into a corporate structure or respond well to what he perceived as Hollywood slickness, so if he was going to be comfortable with selling to Disney, he had to feel like he was dealing with someone who was being authentic and straight with him, and who spoke a language he understood.

Our connection was much more than a business relationship. We enjoyed each other’s company immensely, and we felt we could say anything to each other, that our friendship was strong enough that it was never threatened by candor. You don’t expect to develop such close friendships late in life, but when I think back on my time as CEO—at the things I’m most grateful for and surprised by—my relationship with Steve is one of them. He could criticize me, and I could disagree, and neither of us took it too personally.

Steve Jobs wasn’t a Marvel fan:

When Iron Man 2 came out, Steve took his son to see it and called me the next day. “I took Reed to see Iron Man 2 last night,” he said. “It sucked.”

The Marvel deal draws skeptics:

ON AUGUST 31, 2009, a few months after my first meeting with Ike, we announced we were buying Marvel for $ 4 billion. There were no leaks in advance, no speculation in the press about a possible acquisition. We just made the announcement, then prepared for the backlash: Marvel is going to lose its edge! Disney is going to lose its innocence! They spent $ 4 billion and they don’t have Spider-Man! Our stock fell 3 percent the day we announced the deal.

Jeff Immelt, the CEO of General Electric, which owned NBCUniversal at the time. (Before long, Comcast would buy NBC from them.) Jeff had apparently told Brian that our Marvel deal confounded him. “Why would anyone want to buy a library of comic book characters for $ 4 billion?” he’d said. “It makes me want to leave the business.” I smiled and shrugged. “I guess we’ll see,”

Iger shares his philosophy on firing people:

There’s no good playbook for how to fire someone, though I have my own internal set of rules. You have to do it in person, not over the phone and certainly not by email or text. You have to look the person in the eye. You can’t use anyone else as an excuse. This is you making a decision about them—not them as a person but the way they have performed in their job—and they need and deserve to know that it’s coming from you. You can’t make small talk once you bring someone in for that conversation. I normally say something along the lines of: “I’ve asked you to come in here for a difficult reason.” And then I try to be as direct about the issue as possible, explaining clearly and concisely what wasn’t working and why I didn’t think it was going to change. I emphasize that it was a tough decision to make, and that I understand that it’s much harder on them.

Iger finds a management star who was cast aside by Warner Bros. due to his age:

Bob Daly, who was then co-chair of Warner Bros., called me and said I should talk to Alan Horn about serving as an adviser to Rich. Alan had been pushed out as president and COO of Warner Bros. He was sixty-eight at that point, and though he was responsible for several of the biggest films of the past decade, including the Harry Potter franchise, Jeff Bewkes, Time Warner’s CEO, wanted someone younger running his studio.

Alan eventually agreed, and in the summer of 2012 he came on as the head of Disney Studios. What I saw in him wasn’t just someone who at this late stage in his career had the experience to reestablish good relations with the film community. He also had something to prove. He was galvanized, and that energy and focus transformed Disney Studios when he took over. As I write this, he’s now past seventy-five and is as vital and astute as anyone in the business. He’s been successful in the job beyond all of my hopes. (Of the nearly two dozen Disney films that have earned more than $ 1 billion at the box office, almost three-quarters of them were released under Alan.)

… another lesson to be taken from his hiring: Surround yourself with people who are good in addition to being good at what they do.

The Marvel acquisition was a huge success:

THE ACQUISITION OF Marvel has proved to be much more successful than even our most optimistic models accounted for. As I write this, Avengers: Endgame, our twentieth Marvel film, is finishing up the most successful opening weeks in movie history. Taken together, the films have averaged more than $ 1 billion in gross box-office receipts, and their popularity has been felt throughout our theme-park and television and consumer-products businesses in ways we never fully anticipated.

Iger overrules the skeptics who said Black Panther and Captain Marvel wouldn’t work:

I’ve been in the business long enough to have heard every old argument in the book, and I’ve learned that old arguments are just that: old, and out of step with where the world is and where it should be.

I called Ike and told him to tell his team to stop putting up roadblocks and ordered that we put both Black Panther and Captain Marvel into production.

Black Panther is the fourth-highest-grossing superhero film of all time, and Captain Marvel the tenth. Both have earned well over $ 1 billion.

Chapter 11: Star Wars

Chapter 11 discusses Iger’s long and patient play to acquire Star Wars. The biggest hurdle: George Lucas and the tether of his very identity to the mythology he created.

With every success the company has had since Steve’s death, there’s always a moment in the midst of my excitement when I think, I wish Steve could be here for this.

In the summer of 2011 … We sat in our dining room and raised glasses of wine before dinner. “Look what we did,” he said. “We saved two companies.”

He [Jobs] was convinced that Pixar had flourished in ways that it never would have had it not become part of Disney, and that Disney had been reenergized by bringing on Pixar.

After the funeral, Laurene came up to me and said, “I’ve never told my side of that story.” She described Steve coming home that night. “We had dinner, and then the kids left the dinner table, and I said to Steve, ‘So, did you tell him?’ ‘I told him.’ And I said, ‘Can we trust him?’ ” We were standing there with Steve’s grave behind us, and Laurene, who’d just buried her husband, gave me a gift that I’ve thought about nearly every day since. I’ve certainly thought of Steve every day. “I asked him if we could trust you,” Laurene said. “And Steve said, ‘I love that guy.’ ” The feeling was mutual.

On the day of the rededication of Star Tours in Orlando, I set up a breakfast with him [George Lucas] at the Brown Derby, which was near the attraction in our Hollywood Studios Park.

I asked George if he’d ever thought about selling. I tried to be clear and direct without offending him. He was sixty-eight years old at the time, and I said, “I don’t want to be fatalistic, George, and please stop me if you would rather not have this conversation, but I think it’s worth putting this on the table. What happens down the road? You don’t have any heirs who are going to run the company for you. They may control it, but they’re not going to run it. Shouldn’t you determine who protects or carries on your legacy?” He nodded as I talked. “I’m not really ready to sell,” he said. “But you’re right. And if I decide to, there isn’t anyone I want to sell to but you.”

He said something else that I kept in mind in every subsequent conversation we had: “When I die, the first line of my obituary is going to read ‘Star Wars creator George Lucas…’ ” It was so much a part of who he was, which of course I knew, but having him look into my eyes and say it like that underscored the most important factor in these conversations. This wasn’t negotiating to buy a business; it was negotiating to be the keeper of George’s legacy, and I needed to be ultra-sensitive to that at all times.

About seven months after that breakfast, George called me and said, “I’d like to have lunch to talk more about that thing we talked about in Orlando.”

Lucas had many talented employees, particularly on the tech side, but no directors other than George, and no film development or production pipeline, as far as we knew.

Disney had already begun to assess the value of the Star Wars franchise:

We’d done some work trying to figure out their value ...

Our analysis was built on a set of guesses, and from those we tried to build a financial model—valuing their library of films and television shows; their publishing and licensing assets; their brand, which was dominated by Star Wars; and their special effects business, Industrial Light and Magic, which George had founded years earlier to provide the dazzling special effects for his films. We then projected what we might do if we owned them, which was pure conjecture. We guessed we could produce and release a Star Wars film every other year in the first six years after acquiring them,

Next, we tackled their licensing business. Star Wars remained very popular with kids, particularly young boys, who were still assembling Lego Millennium Falcons and playing with lightsabers.

Lastly, we considered what we might do at our theme parks, given the fact that we were already paying Lucasfilm for the rights to the Star Tours attractions in three of our locations. I had big dreams about what we might build, but we decided to ascribe little or no value to them because there were too many unknowns.

Iger has to reset the acquisition price in Lucas’s mind:

In George’s mind, Lucasfilm was as valuable as Pixar, but even from our relatively uninformed analysis they weren’t.

So I said right away, “There’s no way this is a Pixar deal, George.” And I explained why, recalling my visit to Pixar early on, and the richness of creativity that I discovered.

He was momentarily taken aback, and I thought the discussions might end right there. Instead, he said, “Well, then, what do we do?”

I told him we needed to look closely at Lucasfilm and we needed his cooperation.

I said, “I’m not going to come in low and negotiate toward the middle. I’m going to do it the way I did it with Steve.”

… at the end of that process we still found ourselves struggling to settle on a firm valuation. A lot of our concern had to do with how to assess our own ability to begin making good movies—and quickly.

Ultimately, Kevin and I decided we could afford $ 4.05 billion, or slightly above what we paid for Marvel, and George immediately agreed.

But the most difficult part of the negotiation was personal and emotional—Lucas has to cede control of his creation:

Then the more difficult negotiations began over what George’s creative involvement would be.

With Lucas, there was only one person with creative control—George. He wanted to retain that control without becoming an employee.

… his entire self was wrapped up in the fact that he was responsible for what was perhaps the greatest mythology of our time. That’s a hard thing to let go, and I was deeply sensitive to that.

I also knew we couldn’t spend this money and do what George wanted, and that saying that to him would put the whole deal at risk. That is exactly what happened.

… twice [the parties] walked away from the table and called the deal off. (We walked the first time and George walked the second.)

George told me that he had completed outlines for three new movies.

we needed to buy them, though we made clear in the purchase agreement that we would not be contractually obligated to adhere to the plot lines he’d laid out.

Negotiations were stuck. But tax law saved the day:

an upcoming change in capital gains laws that eventually salvaged the negotiations. If we didn’t close the deal by the end of 2012, George, who owned Lucasfilm outright, would take a roughly $ 500 million hit on the sale.

he reluctantly agreed to be available to consult with us at our request. I promised that we would be open to his ideas (this was not a hard promise to make; of course we would be open to George Lucas’s ideas), but like the outlines, we would be under no obligation.

On October 30, 2012, George came to my office, and we sat at my desk and signed an agreement for Disney to buy Lucasfilm. He was doing everything he could not to show it, but I could tell in the sound of his voice and the look in his eyes how emotional it was for him. He was signing away Star Wars, after all.

After the acquisition, the creative development process is rocky:

A FEW MONTHS before we closed the deal, George hired the producer Kathy Kennedy to run Lucasfilm.

this was one final way for George to put someone in whom he trusted to be the steward of his legacy.

J.J. and I had dinner soon after he decided to take on the project.

I joked at some point during dinner that this was a “$ 4 billion movie”—meaning that the whole acquisition depended on its success—which J.J. later told me wasn’t funny at all.

There’s no rule book for how to manage this kind of challenge, but in general, you have to try to recognize that when the stakes of a project are very high, there’s not much to be gained from putting additional pressure on the people working on it.

Early on, Kathy brought J.J. and Michael Arndt up to Northern California to meet with George at his ranch and talk about their ideas for the film. George immediately got upset as they began to describe the plot and it dawned on him that we weren’t using one of the stories he submitted during the negotiations.

we all agreed that it wasn’t what George had outlined. George knew we weren’t contractually bound to anything, but he thought that our buying the story treatments was a tacit promise that we’d follow them,

I could have handled it better.

I should have prepared him for the meeting with J.J. and Michael and told him about our conversations, that we felt it was better to go in another direction.

George felt betrayed ...

Just prior to the global release, Kathy screened The Force Awakens for George. He didn’t hide his disappointment. “There’s nothing new,” he said. In each of the films in the original trilogy, it was important to him to present new worlds, new stories, new characters, and new technologies. In this one, he said, “There weren’t enough visual or technical leaps forward.”

Looking back with the perspective of several years and a few more Star Wars films, I believe J.J. achieved the near-impossible, creating a perfect bridge between what had been and what was to come.

Shortly after the release, though, an interview George had done a few weeks earlier with Charlie Rose aired. George talked about his frustration that we hadn’t followed his outlines and said that selling to Disney was like selling his children to “white slavers.” It was an unfortunate and awkward way for him to describe the feeling of having sold something that he considered his children. I decided to stay quiet and let it pass. There was nothing to be gained from engaging in any public discourse

George called me. “I was out of line,” he said.

Though each major acquisition, a common trait saved negotiations:

Looking back on the acquisitions of Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm, the thread that runs through all of them (other than that, taken together, they transformed Disney) is that each deal depended on building trust with a single controlling entity.

Chapter 12: If You Don’t Innovate, You Die

Chapter twelve discusses Iger’s strategy to create and deploy a direct-to-consumer service: a Netflix competitor which would eventually become Disney+.

AFTER THE DUST settled on the last of our “big three” acquisitions, we began to focus even more on the dramatic changes we were experiencing in our media businesses and the profound disruption we were feeling. The future of those businesses had begun to seriously worry us, and we concluded it was time for us to start delivering our content in new and modern ways, and to do so without intermediaries, on our own technology platform.

Disney goes through a build-vs-buy decision process:

We landed on Twitter. We were less interested in them as a social media company than as a new distribution platform with global reach, which we could use to deliver movies, television, sports, and news.

Twitter’s board supported the sale, and on a Friday afternoon in October, our board gave their approval

Iger’s gut feeling to kill the deal is prescient—Twitter’s issues would have been devastating to the Disney brand.

Something inside me didn’t feel right. Echoing in my head was something Tom Murphy had said to me years earlier: “If something doesn’t feel right to you, then it’s probably not right for you.” I could see clearly how the platform could work to serve our new purposes, but there were brand-related issues that gnawed at me.

I couldn’t get past the challenges that would come with it.

how to manage hate speech,

making fraught decisions regarding freedom of speech,

fake accounts algorithmically spewing out political “messaging”

and the general rage and lack of civility

I felt they would be corrosive to the Disney brand.

Disney moves on to Plan B.

AROUND THE SAME TIME that we entered into the Twitter negotiations, we also invested in a company called BAMTech, which was primarily owned by Major League Baseball and had perfected a streaming technology that allowed fans to subscribe to an online service and watch all of their favorite teams’ games live.

… we agreed to pay about $ 1 billion for a 33 percent stake in the company, with an option to buy a controlling interest in 2020.

Ten months later, in June 2017, we held our annual board retreat … We decided to spend the entire 2017 session talking about disruption …

I don’t like to lay out problems without offering a plan for addressing them.

We would accelerate our option to buy a controlling stake in BAMTech, and then use that platform to launch Disney and an ESPN direct-to-consumer, “over the top” video streaming services.

On our August 2017 earnings call … we shared our plans to launch two streaming services: one for ESPN in 2018, and one for Disney in 2019.

Iger moves from plan to execution—and must remake Disney’s culture and strategic priorities to make it work:

THAT ANNOUNCEMENT MARKED the beginning of the reinvention of the Walt Disney Company.

… we were now hastening the disruption of our own businesses, and the short-term losses were going to be significant.

I referred to a concept I called “management by press release”—meaning that if I say something with great conviction to the outside world, it tends to resonate powerfully inside our company.

We immediately began working on two fronts in the wake of our August announcement. On the tech side, the team at BAMTech, along with a group that was already in place at Disney, started building the interfaces for our new services,

At the same time, back in L.A., we were putting a team together to develop and produce the content that would be available on Disney +.

I proposed a radical idea—essentially, that I would determine compensation, based on how much they contributed to this new strategy, even though, without easily measured financial results, this was going to be far more subjective than our typical compensation practices.

“I know why companies fail to innovate,” I said to them at one point. “It’s tradition. Tradition generates so much friction, every step of the way.”

Chapter 13: No Price no Integrity

Chapter 13 discusses Iger’s ethical challenges within the Disney culture, as talented executives make personal mistakes that harm others, and themselves. While dealing with those issues, Iger has to remake the company in response to technology disruptions which force Disney to change its creative and distribution processes.

RUPERT’S DECISION TO sell was a direct response to the same forces that led us to create an entirely new strategy for our company. As he pondered the future of his company in such a disrupted world, he concluded the smartest thing to do was to sell and give his shareholders and his family a chance to convert its 21st Century Fox stock into Disney stock, believing we were better positioned to withstand the change and, combined, we’d be even stronger.

In the fall of 2017, we heard complaints about John Lasseter from women and men at Pixar, about what they described as unwanted physical contact.

Alan Horn and I met with John in November of that year, and together we agreed that the best course was for him to take a six-month leave to reflect on his behavior and give us time to assess the situation.

As Disney was about to announce its acquisition of Fox, Iger is blindsided by ESPN president John Skipper’s issues:

December 14 ranks as another of the most compartmentalized days of my career.

GMA announcement at 4:00 A.M.

Conference call with investors at 5:00 A.M.

CNBC Live at 6 00 A.M.

Bloomberg at 6:20 A.M.

Webcast with investors at 7:00 A.M.

From 8:00 A.M. till noon were calls with Senators Chuck Schumer and Mitch McConnell, then Representative Nancy Pelosi and several other members of Congress, in anticipation of the regulatory process that was about to unfold.

… that afternoon, Jayne came into my office to have the conversation that we’d punted on the day before. She told me that John Skipper had admitted to a drug problem, which had led to other serious complications in his life and could potentially jeopardize the company.

Following the acquisition, Iger again sets out to reset Disney’s culture and structure:

I asked myself: What would, could, or should the new company look like? If I were to erase history and build something totally new today, with all of these assets, how would it be structured? I came back from our Christmas holiday and dragged a whiteboard into the conference room next to my office and began to play around. (It was the first time I’d stood before a whiteboard since I was with Steve Jobs in 2005!)

The first thing I did was separate “content” from “technology.” We would have three content groups: movies (Walt Disney Animation, Disney Studios, Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, Twentieth Century Fox, Fox 2000, Fox Searchlight), television (ABC, ABC News, our television stations, Disney channels, Freeform, FX, National Geographic), and sports (ESPN). All of that went on the left side of the whiteboard. On the other side went tech: apps, user interfaces, customer acquisition and retention, data management, sales, distribution, and so on. The idea was simply to let the content people focus on creativity and let the tech people focus on how to distribute things and, for the most part, generate revenue in the most successful ways.

Chapter 14: Core Values

Chapter 14 is the wrap-up chapter; Iger looks back at his tenure from a high view, and realizes his time at Disney will soon be over.

The intensity of the work didn’t fully inoculate me against a kind of wistfulness creeping in, though. The future that we were planning and working so feverishly on would happen without me. My new retirement date is December 2021, but I can see it out of the corner of my eye. It surfaces at unexpected times. It’s not enough to distract me, but it is enough to remind me that this ride is coming to an end. As a joke a few years back, dear friends of mine gave me a license plate holder, which I immediately attached to my car, that says, “Is there life after Disney?” The answer is yes, of course, but that question feels more existential than it used to.

Even when a CEO is working productively and effectively, it’s important for a company to have change at the top. I don’t know if other CEOs agree with this, but I’ve noticed that you can accumulate so much power in a job that it becomes harder to keep a check on how you wield it. Little things can start to shift. Your confidence can easily tip over into overconfidence and become a liability.

The Ride of Lifetime Appendix: Lessons to Lead By

The appendix offers condensed versions of the leaderships lessons Iger shared in the book.

AT THE END of this book on leadership, it struck me that it might be useful to collect all of these variations on the theme in one place.

To tell great stories, you need great talent.

innovate or die.

“the relentless pursuit of perfection.”

creating an environment in which people refuse to accept mediocrity.

Take responsibility when you screw up.

Be decent to people.

Excellence and fairness don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

True integrity—a sense of knowing who you are and being guided by your own clear

sense of right and wrong—is a kind of secret leadership weapon.

Value ability more than experience,

Managing creativity is an art, not a science.

Don’t start negatively, and don’t start small.

if you want innovation, you need to grant permission to fail.

Don’t be in the business of playing it safe.

Don’t let ambition get ahead of opportunity. By fixating on a future job or project, you become impatient with where you are.

He was telling me not to invest in small projects that would sap my and the company’s resources and not give much back.

When the people at the top of a company have a dysfunctional relationship, there’s no way that the rest of the company can be functional.

As a leader, if you don’t do the work, the people around you are going to know, and you’ll lose their respect fast.

be self-aware enough that you don’t cling to the notion that you are the only person who can do this job.

demand integrity from your people and your products at all times.

Michael Eisner used to say, “micromanaging is underrated.” I agree with him—to a point.

Too often, we lead from a place of fear rather than courage,

No one wants to follow a pessimist.

Optimism emerges from faith in yourself and in the people who work for you.

Long shots aren’t usually as long as they seem.

convey your priorities clearly and repeatedly.

messaging is fairly simple: This is where we want to be. This is how we’re going to get there.

It should be about the future, not the past.

It’s easy to be optimistic when everyone is telling you you’re great.

Treating others with respect is an undervalued currency when it comes to negotiating.

You have to do the homework.

If something doesn’t feel right to you, it won’t be right for you.

As a leader, you are the embodiment of that company.

In any negotiation, be clear about where you stand from the beginning.

Projecting your anxiety onto your team is counterproductive.

Most deals are personal.

making something, be in the business of making something great. The decision to disrupt a business model that is working for you requires no small amount of courage.

It’s not good to have power for too long.

approach your work and life with a sense of genuine humility.

Hold on to your awareness of yourself.

You can pick up The Ride of a Lifetime from Amazon today.

Star Wars novels: where should a new reader start?

How people look at me when they find out I’ve read over 30 Star Wars novels:

Hey, we all have our quirks. People have far weirder habits, which will not be discussed in detail here, because this is a family blog.

But why read so many Star Wars books, nerd man?

The simple answer is I like reading, and I like Star Wars. Peanut butter and jelly. Secondly, I have a weird personal dichotomy: I hate clutter, but like collecting stuff. Books provide a balance to this. You can collect them and store them in a pretty orderly fashion. And finally, it’s fun. Fun is still ok, right?

So, where should a new reader start?

Before I make suggestions, you need to understand something about the universe of Star Wars novels.

Disney drew a line of demarcation amongst the Star Wars books when it purchased the franchise in 2012. Prior to Disney’s purchase, well over 100 novels had already been published. The storylines were wild, and sometimes contradictory:

Chewbacca was dead, squished in a collision of planets (seriously).

Luke had a Jedi wife.

Leia was a Jedi Knight.

And on and on it went. Total space chaos.

And while many of those stories were fun, they were a nightmare for Disney, which was preparing to rake in obscene piles of cash with a sequel trilogy. There was no coherent way for Disney to move the Star Wars story forward on-screen in a way that upheld the stories in the books.

So Disney declared all the books that came before its purchase “Legends,” which meant they didn’t count as canon. They became rumors and fairy tales.

All the books published after the Disney purchase count as canon, and Lucasfilm has a story group — “Storytroopers,” if you will — that enforce story continuity and character development. All the books and comics must now support Star Wars films and TV series, and vice versa.

With that distinction made, I have three recommendations for a new reader:

Resistance Reborn, by Rebecca Roanhorse

Resistance Reborn is the newest Star Wars novel. The book acts as the Avengers Endgame of new canon era of Star Wars novels, drawing in characters from numerous earlier books. Not only do we get to see what Leia, Rey, Poe, Finn, and Chewbacca are up to after the the events of the Last Jedi, we also get updates from new characters created in the latest novels, comics, and even video games:

Yes, we’ve got Norra Wexley and her son Snap (Temmin, as he went by before he became Greg Grunberg) to represent the Aftermathbooks, or figures like Bloodline’s Ransolm Casterfo and Lost Stars’ Twi’lek pilot-turned-ambassador Yendor, who become crucial allies to the Resistance’s cause. But Resistance Reborn reaches wider—and in doing so feels like a satisfying love letter to every corner of what’s come so far in this new version of the Star Warsgalaxy.

From Marvel’s comics, there are characters like Karé Kun and Suralinda Javos from Charles Soule, Phil Noto, and Angel Unzueta’s fabulous Poe Dameron comic(the former introduced briefly in the anthology novella Before the Awakening, but fleshed out more completely in Marvel’s work). From EA’s video games, we get Zay Versio, daughter of Iden, and Shriv the Duros from Battlefront II’s story campaign.

The book opens moments after the Resistance escapes at the end of The Last Jedi, as the decimated force regroups and calls on old allies to rally for what is to come in The Rise of Skywalker.

A reader new to Star Wars novels not only gets an entertaining book featuring familiar characters, but also an introduction to characters created in the new “Disney cannon” era of Star Wars books. Double win. Start here.

Lost Stars, by Claudia Gray

Lost Stars sits in the “young adult” sub-genre of Star Wars fiction. And it’s a romance-adventure -- a rarity among Star Wars books.

So this YA romance novel is among the best in the Star Wars genre?

Absolutely.

Lost Stars follows the life stories of Ciena Ree and Thane Kyrell, from childhood up through their military careers as ace pilots--except one flies for the Empire, and the other for the Rebellion.

And that Star Destroyer you see crashing? It’s the same one shown to us in the opening of the epic The Force Awakens trailer--the one crashed on Jakuu, where Rey later explores and finds metal to trade for rations. It’s a cool tie-in.

Lost Stars covers a lot of ground, from the time of A New Hope up past Return of the Jedi, and while the main characters change and grow, their affection for one another remains steady, no matter how they fight it, and each other.

Kenobi, by John Jackson Miller

Finally, a recommendation from the Legends Era of Star Wars novels. John Jackson Miller’s Kenobi was publsihed in 2013.

And even though this book isn’t canon, we will no doubt see some of its themes in the upcoming Kenobi TV series on Disney+.

Miller writes an old-west-style tale of Obi Wan Kenobi living in the desert of Tatooine after the fall of the Republic. Kenobi tries to live a quiet life in the shadows to watch over young Luke Skywalker from a distance.

Of course, Obi Wan being Obi Wan, he gets involved with all kinds of shady characters and dangerous creatures and does lots of wild Jedi things.

So there you have it. If you’re new to the Star Wars novel universe, then try starting here and see if you get hooked. Who knows—someday you may have read 30 Star Wars novels, too. And you can get weird looks, just like me.

The Pathway to Personal Reinvention

Trust me on this.

At some point, in your personal or professional life, you will have to pivot. The identity you had, the work you did, will no longer serve you.

It will be time to reinvent yourself. And the timing may not be to your liking.

You Are a Brand

Tom Peters popularized the idea of “Personal Brands” way back in the Internet boom—the “real” one, in the late 90s, with dial-up service, Geocities, and sock-puppet Super Bowl commercials—with an article and cover story in Fast Company Magazine, which, in those days, was about the size of a phone book.

(Note to younger readers: a phone book is … never mind. Just Google it.)

From the classic article “A Brand Called You”:

It’s time for me — and you — to take a lesson from the big brands, a lesson that’s true for anyone who’s interested in what it takes to stand out and prosper in the new world of work.

Regardless of age, regardless of position, regardless of the business we happen to be in, all of us need to understand the importance of branding. We are CEOs of our own companies: Me Inc. To be in business today, our most important job is to be head marketer for the brand called You.

This article made a big splash in 1997. It was true then—and, although some of the methods have changed (consultants probably don’t need CEOs to memorize their beeper numbers)—the principles are more relevant than ever:

You don’t “belong to” any company for life, and your chief affiliation isn’t to any particular “function.” You’re not defined by your job title and you’re not confined by your job description.

Brands evolve (if they want to survive). Your brand needs to evolve, too.

Maybe your evolution is a just a nudge, a tiny course alteration.

Or maybe it’s time for something bigger. You’re not quite sure what that change is, but you know you need it.

In that case, welcome to the wilderness. Welcome to …

The Wandering

Dorie Clark wrote a classic piece on personal reinvention in Harvard Business Review. But I strongly disagree with this part:

What’s Your Destination? First, you need to develop a detailed understanding of where you want to go, and the knowledge and skills necessary to get there.

Nope. The “detailed understanding” does not come first.

First is The Wandering.

Wandering is movement, but without clear direction.

You have to reinvent out loud and in motion -- you can’t think your way to reinvention.

That makes it more stressful, of course. You won’t know where you’re going when you start. You have to try things out, start and stop, and listen to your inner compass.

The fits and starts are a necessary toll extracted for finding the path. So let yourself try out some different ideas. Like the legendary Gerry Rafferty said, “If you get it wrong you’ll Get it Right Next Time.”

And it can take a long time to get it right.

More from Tom Peters:

It’s over. No more vertical. No more ladder. That’s not the way careers work anymore. Linearity is out. A career is now a checkerboard. Or even a maze. It’s full of moves that go sideways, forward, slide on the diagonal, even go backward when that makes sense. (It often does.) A career is a portfolio of projects that teach you new skills, gain you new expertise, develop new capabilities, grow your colleague set, and constantly reinvent you as a brand.

“Reinvention” is often an excavation project. We have to shed the expectations of others, particularly in service of a specific corporate role. We have to shed the expectations of ourselves, often implanted in school or by society.

What do you really want to do? How—and whom—do you really want to serve?

I can’t imagine reinvention without a spiritual foundation.

The danger in proceeding without spiritual belief is you’re more likely to head down the wrong path—one that just serves your ego, or pleases another person or group you may not even consciously realize you’re trying to please.

You run the risk of ending up on the wrong path, unhappier and less fulfilled than ever.

Aim to serve something bigger than yourself.

And then … eventually … you’ll start to know where you’re headed.

You might even have an “Oh, I knew that all along” moment.

You can see the path, and now comes …

The positioning

Your new path might feel far from the person you were and the experiences you’ve had. But it’s probably not as far as you think.

Clark discusses leveraging your past to serve your new positioning:

Develop a Narrative. You used to write award-winning business columns — and now you want to review restaurants?

[...]

It’s unfair, but to protect your brand you need to develop a coherent narrative arc that explains to people — in a nice, simple way so they can’t miss it — exactly how your past fits into the present. “I used to write about the business side of many industries, including food and wine,” you could say. “I realized my big-picture knowledge about agricultural trends and business finance made me uniquely positioned to cover restaurants with a different perspective.” It’s like a job interview — you’re turning what could be perceived as a weakness (he doesn’t know anything about food, because he’s been a business reporter for 20 years) into a compelling strength that people can remember (he’s got a different take on the food industry because he has knowledge most other people don’t).

Change the way you think about your experience and your resume.

A resume doesn’t exist on a stone tablet, an Eternal Truth chiseled in granite to be preserved and handed down for generations.

Instead, your resume is a story that evolves to suit your changing goals and direction.

Career expert Penelope Trunk:

Life is messy and it is not black and white. There is no single, correct story about your life. Because each moment, in each person’s life, has multiple versions, all true.

The biggest problem people have when they are changing careers, or moving up the ladder, or re-entering the workforce, is that they cannot imagine telling a completely different story about themselves than they have been telling for the last ten years.

Did you know that my resume can tell the story of me as a writer or me as an operations genius? I don’t like operations, but if I had to get a job in operations, I could write my resume to indicate that operations has been my focus for the last fifteen years. And I wouldn’t have any lies on my resume. I’d just frame the truth in a different way.

Whatever your new path is, you have related experience that lends credibility to that path. Use it.

Put another way:

Don’t expect to fully “reinvent”: While the concept of “reinvention” is tantalizing (think: “fresh slate” “unrealized dreams” etc.), most people don’t construct a new career from scratch at midlife. The stories you read about the accountant turned cattle rancher – or the doctor turned vineyard owner – make for great press, but they are the exception, not the norm. In reality, most people choose a second-act career that is in some small way, shape or form related to what they did before. They figure out which parts of their old career they most enjoy (skills, people, industry, etc.) and then blend the “old” pieces with “new” interests, hobbies, and passions.

Just Keep Going

(Or, you know, swimming.)

This reinvention thing—it’s exhausting, frustrating, and, hopefully, exhilarating. We only see the “after” stories of triumph and happiness and unicorns, etc.

We don’t see the long slog to get there.

But the world has never been hungrier, or offered more opportunity, for authenticity. If you need to shift, you can. You can find a market to serve. You can find your authenticity and make your way.

There are many examples of this today:

A teacher turned full-time online fitness coach

marketing agency employee turned SEO consultant and teacher:

And an extreme example: Steve Ballmer, maniacal raving CEO of Microsoft …

became Steve Ballmer, maniacal raving owner of the Los Angeles Clippers, where he’s stealing all the buzz and cache from the rival Lakers.

People turn themselves inside out and find unique and authentic ways to impact the world and make a living.

You can, too.If you’re struggling with reinvention, I’ll leave you with something Steven Furtick of Elevation Church conveyed in a sermon called “Trapped in Transition:”

“God is most active in moments of what I perceive to be instability and transition”

So just keep going (swimming).

You’re not alone, and you’re on the right path, even if you can’t see the path yet.

Thanks for reading! If you found this useful, I’d appreciate it if you’d sign up for my

weekly newsletter, The Mix Tape.

Improving Email Newsletter signup conversions

Email newsletters are still a great way to connect with customers, prospects, partners, and others in your network.

But growing an email newsletter subscriber base is a long slog. Nailing the basics of newsletter conversions on your site makes the slog a bit easier.

Marketing Examples shares the basics of improving on-site newsletter signup conversions:

Choosing whether or not to subscribe to an email list is a split-second decision. This means that subtle psychological tweaks can make a big difference.

Here’s the checklist:

1) Make it obvious

2) Use an exit-intent popup

3) Get a subscribe page

4) Ask as a human

5) Give a clear reason to sign up

6) Add Social Proof

7) Use value-based messaging

After reading the case study, I realized I had work to do. So let’s get to it, and you can learn and implement along with me.

The newsletter signup page

My newsletter signup page has been revamped (subject to ongoing additional revampage, of course).

The signup page changed from this:

To this:

So what’s the thinking behind the change?

Make it personal: “A weekly mix of what I’m learning about” was moved into the sub-headline, followed by some sample topics.

Social proof: The testimonial conveys that there is value in subscribing. Sharing the open and unsubscribe rates lends additional credibility.

CTA: I had a little fun here with the subscribe button, changing from “subscribe” to (Light) rock my inbox,” which ties to the copy above. A more value-based approach (“Rock my marketing,” “Rock my SEO” might be stronger.

Exit-intent newsletter pop-ups

In the Marketing Examples case study, 55% of new subscribers are attributed to an “exit-intent” pop-up, which appears when the user’s cursor moves off the browser display and up to the tabs or address bar.

Unfortunately, Squarespace (which I use for this site) doesn’t support exit-intent pop-ups out-of-the-box, (wow, that was a lot of dashes...) but you can still add pop-ups to a Squarespace site:

Even though you can’t implement the true exit pop-up strategy, you can control timing to an extent. So I set mine up to trigger after either:

Five seconds pass, or

The user scrolls down more than 25% of the page

Newsletter sign up thank you page

After a user subscribes (yes!) you can further build the relationship and support the user’s decision with a thank you page.

With a thank you page, you should:

Thank the person for subscribing (duh).

Offer instructions to help deliverability, such as asking them to add your email address to their contact list.

Offer a surprise. This can be a “freebie,” like a special report, or even something more simple. I just asked if the person wanted to take a breather and listen to “Deacon Blues,” the best song of the 1970s.

(It is the best. Just saying.)

The thank you page is important, because of the next step …

Tracking newsletter signup conversions in Google Analytics

Now that we have the thank you page in place, tracking conversions becomes pretty simple in Google Analytics:

From the Analytics homepage, click “Conversions.”

Click “goals” from the sub-menu.

Ciick “Overview: from the sub-menu.

Click the button on the right that says “Set up Goals.”

Click the red button that says “NEW GOAL.”

Under acquisition, click “Create an Account.”

Name the goal in the box provided (try something wild like “Newsletter signups.”

“Destination” will be pre-selected in the menu below. This is good. Hit continue.

Under “goal details” enter the URL of your thank you page in the first box (just to the right of “equals to.”

Hit save.

That looks like a longish list, but it’s a quick process.

Now Google will give you reports on conversion: the percentage of site visitors who take the signup action by dividing thank you page views by total visitors over a given time period.

With the conversion basics in place, track and test

Now that you have the basics in place, watch conversions—both total conversions over time and conversion rate—and experiment. Sometimes tweaking a headline or a graphic can make a big difference, and you’ll never know for sure unless you test.

Bonus: promoting your newsletter with tagging

Obviously you want to promote your newsletter through your social accounts. But I liked this sign-up boosting tip shared by Sarah Noeckel, who has grown her newsletter to more than 5,000 subscribers:

In other words, when you share links to other articles, videos, etc. in your newsletter, tag the content creators when you promote the newsletter in social media.

Like this:

Good luck! Let me know what’s working well for you.

Thanks for reading! If you found this useful, I’d appreciate it if you’d sign up for my

weekly newsletter, The Mix Tape.

Book review: Star Wars: Master and Apprentice, by Claudia Gray

“Darkness is a part of nature, too, Qui-Gon. Equally as fundamental as the light. Always remember this.”

—Master Dooku

Good Star Wars novels feature an interesting story that generally checks a few important boxes. They will:

Deepen and alter our understanding of existing Star Wars canon. By revealing new details or a fresh perspective on existing canon, the book rewards the reader. We learned something new, and are smarter for it.

Center around well-known and beloved characters.

Introduce new characters in service of the main storyline and the well-known characters without dragging the reader off on bunny trails.

Some recent Star Wars novels have swung and missed at one or more of these key tenants.

But not Claudia Gray’s Master and Apprentice. The book is fun. Which, you know, was once the point of Star Wars.

(Interestingly enough, another of Claudia Gray’s Star Wars books—“Lost Stars”—focuses largely on new and unknown characters, and it’s a great book. Exception to every rule.)

”Master and Apprentice” provides:

An interesting story, as Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon are sent on a mission that morphs into something quite different--and more dangerous--than they expected.

An emphasis on action and on Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon’s relationship. The master and padawan, while dealing with external chaos and uncertainty, also have to deal with the exact same problems in their own struggles to work together cohesively.

Secondary characters that serve the story and main characters—an old Jedi turned planet-ruler, jewel thieves, a young princess coming into her own—these and other characters and others keep the book moving in an interesting fashion, and keep the spotlight where it belongs: on Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon.

New understanding of Star Wars canon in a few ways, including:

Insight into Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan’s relationship as Master and Padawan—and it ain’t smooth sailing.

How the pursuit of prophetic knowledge (including ancient Jedi prophecy) affects Jedi for better and for worse.

As a bonus, the new characters are interesting, with creative backgrounds that also serve Star Wars history—and the characters surprise us as the story unfolds.

Gray always delivers a good Star Wars tale, and this one is no different. A Star Wars novel should leave you, as a fan, entertained and enlightened. “Master and Apprentice” delivers.

Thanks for reading! If you liked this, I’d appreciate it if you’d sign up for my weekly newsletter, The Mix Tape.

The Best SEO Newsletters of 2019

SEO newsletters help you stay on top of new developments, pick up new ideas, and even network with other professionals. Here are some of the best SEO newsletters of 2019, in no particular order.

Marketing Examples

Harry covers SEO and much more in his excellent, real-world-example-driven newsletter, and we can all better marketers for it. He shares case studies with straight-forward, actionable steps.

Sign up for Marketing Examples

Search Engine Land

Daily updates with quick news and tips. Always something in there worth a click.

Get the daily newsletter here.

Total Annarchy

For content strategy and just-plain-better-writing-strategy, get Ann Handley’s bi-weekly Total Annarchy. Handley, a WSJ best-selling author and MarketingProfs partner, has an easy, conversational writing style.

(Also, this one takes first place in the Best Newsletter Name category.)

SEO by the Sea

Bill Slawski focuses on, as he puts it, “SEO as the search engines tell us about it, from sources such as patents and white papers from the search engines.”

Slawski has worked in SEO since 1996, and knows a thing or two because he’s seen a thing or two.

Content Marketing Institute newsletter

The Content Marketing Institute was founded in 2011 by Joe Pulizzi, and is a powerhouse of events and content focused on—wait for it—content.

Get the Content Marketing Institute newsletter here.

Bonus: CMI publishes a digital magazine called “CCO” that publishes in March, July, and October.

Moz Top 10

A semi-monthly newsletter with “the ten most valuable articles about SEO and online marketing that we could find” from the Moz SEO software powerhouse.

SEO Roundtable

The SEO Roundtable surfaces the most interesting topics in the hreads taking place at the SEM (Search Engine Marketing) forums.

Content is powered by Barry Schwartz, CEO of RustyBrick, and stays right on top of the latest SEO developments.

Get the SEO Roundtable newsletter here.

TL;DR Marketing

The second best newsletter name on this list (after Total Annarchy), TL;DR Marketing brings the SEO thunder from down under.

Sign up for the TL;DR newsletter here, or check out a past edition.

Blind Five Year Old

This one doesn’t come out on a consistnet basis, but when it does, A.J. Kohn packs it full of value and insight.

The name?

Well, A.J. says:

The strange name comes from a specific search engine optimization (SEO) philosophy – to treat search engines like they are blind five year olds.

Sign up for the Blind Five Year Old newsletter here.

Gaps.com

Glenn Allsopp is remarkable. He’s an SEO expert, an excellent writer, and a creative and diligent researcher who uncovers angles and opportunities no one else does.

Don’t hesitate—just sign up.

Kaiserthesage

Tested and actionable content on SEO, content marketing, and link building from Jason Acidre – a Manila-based Digital Marketing Consultant.

Sign up for KaisertheSage here.

A bonus for the best SEO newsletters list: Morning Brew

Morning Brew is a daily email that isn’t SEO focused but gives you a quick and entertaining rundown on the big business stories of the morning.

It’s so well-written I have to include it, and it’s great for SEO pros who want to keep up on the big business stories without wasting a lot of time reading or watching news.

(Note: This is my Morning Brew referral link. I might, someday in a bright and distant future, earn stickers or a coffee mug or if you subscribe.)

If you found this “Best SEO Newsletters” compilation helpful, I’d appreciate if you’d consider subscribing to my newsletter, The Mix Tape (if you haven’t already). Thanks!

Squarespace SEO: A Quick Audit Process

Squarespace SEO sometimes gets a bad rap, but the web site creation and hosting service offers the features needed to create a solid SEO foundation.

In this article, I’ll walk you through some of the basics to review and improve SEO within your Squarespace site, giving you a launching pad to branch out into longer-term content and link-building strategies to grow your audience.

Squarespace SEO tools

Before we get started, here’s a list of the tools I’ll be referencing today:

Google Analytics : The mack-daddy, commonly-used free analytics toolset from Google.

Google Webmaster Tools: Lets you see your site the way Google sees it, to spot errors and looks for areas to improve.

Screaming Frog: is a “crawler” that reviews and analyzes sites, and it’s free for sites with less than 500 web pages. (If you’re new to the tool, here’s an excellent Screaming Frog tutorial for beginners.)

Siteliner: A tool for finding duplicate content on your site.

Squarespace Analytics: The Analytics package provided by Squarespace (also available in a nice iOS app.)

TinyPNG: Allows you to compress (reduce the file size) of images so web pages load faster. Google likes fast web pages. You can upload and compress 20 image files at a time.

Website Planet image compressor: An alternative to TinyPNG.

Your Squarespace analytics

Squarespace has a pretty good internal analytics package that covers the basics, and an accompanying iOS app that’s easy to use.

But if you haven’t already done so, set up your Google Analytics account, as it allows you to drill down much deeper depending on the goals for your site.

(This Squarespace tutorial walks you through setting up your Google Analytics account and connecting it to your website.)

Once set up, copy your Google Analytics Account number into the box provided inside Squarespace located at Settings > Advanced > External API Keys.

Tip: Make sure you log in—and stay logged in—to Squarespace on any browser you use (desktop and phone) to exclude your own site activity from your analytic stats. Otherwise, every time you visit your own site, your activity will be tracked as a visitor in Squarespace’s analytics package.

Squarespace website architecture

Your site should be as lean and logically structured as possible. An ideal website structure starts at the homepage, has a handful of key sections highlighted in home page navigation, and has nearly all other pages “nested” within those sections.

A typical site structure for a personal or small business Squarespace site might look something like this:

The top level is your home page.

At the second level are your main section areas, in this case:

About

Services

Newsletter

Blog

These sections are “nested” under the home page, and would appear in the main navigation menu on the home page.

Don’t go too crazy with categories--seven is really the limit, and less is usually better for the user experience.

Beneath these sections are third-level pages, which here includes blog posts and individual pages describing the services offered.

Everything flows down from the home page, and “child” pages are nested under their parents.

Tip: Do not nest at more than three levels if possible. After three levels, Google views pages as less important, decreasing the ranking potential of the lower-level pages.

URL structure

Your site’s URL structure should match your site hierarchy

For example, the URL for the “Blog Post 1” page in the example above should look like this:

www.URL.com/blog/blog-post-1

The URL for the “Service Two” page should look like:

www.URL.com/services/service-2

Example: My site

At my site, the categories beneath the home page include:

About

Blog

Book notes

SEO notes

Newsletter signup

But my URL structure didn’t reflect my site structure, and I had work to do.

My third-level book notes pages were set up like this:

www.matttillotson.com/booknotes-book-title-author, which makes the section structure unclear.

The fix required two steps.

First, I changed the URL of the book notes overview page to:

www.matttillotson.com/book-notes

And then the URLs of book notes pages themselves (as children of the book notes overview page) are set up as:

www.matttillotson.com/book-notes/title-author

That structure communicates the correct site hierarchy to Google.

Keep URLs concise, and, after reflecting site structure, as limited to the keyword or keywords for that page as possible.

For example, using our site map example above, a page in the services section detailing purple widget repair should use the URL:

www.URL.com/services/purple-widget-repair

There’s no perfect answer on URL length, but generally aim for 50-60 characters.

Remember: Changing URLs will break links—both links you have internally on your own site, and external links from other sites to yours). More on how to fix that later.

Links

Links tell Google important things about the authority of your site and individual pages and can help search ranking.