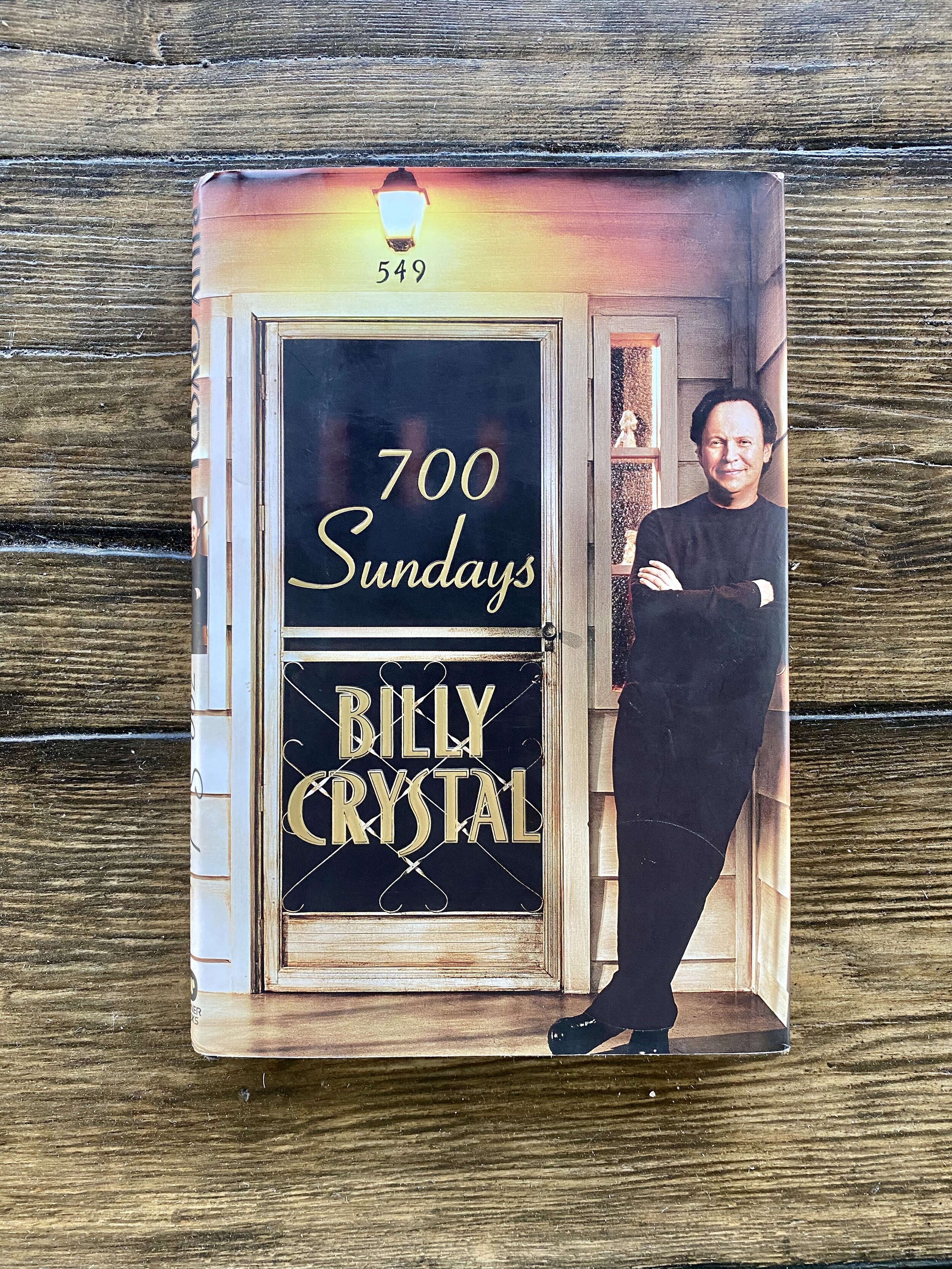

Review and highlights: 700 Sundays, by Billy Crystal

700 Sundays is not the book I anticipated.

It’s written by Billy Crystal, so it’s hilarious, right?

Crystal sprinkles humor into his autobiography. But the book is—while not altogether dark—colored with sadness.

The book’s title comes from the number of Sundays Crystal had with his father, Jack, before Jack died suddenly of heart attack, in a bowling alley. Bill Crystal was 15. Jack was 56.

Jack Crystal lived a unique and interesting life, running a small record store, producing jazz records on the family label (“Commodore”) and running concerts for some of the greatest jazz musicians of the 50s and 60s:

So when I was a kid growing up, my father was now managing the Commodore Music Shop and he had become the authority on jazz and jazz records in the city. And this little store—it was only nine feet wide—was now the center of jazz not only in New York City but in the world, because that little mail order business was now third worldwide behind Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward, just selling Commodore and other jazz records.

Commodore’s roster included Billie Holliday, who recorded “Strange Fruit” on the label, which Time Magazine later called the song of the century:

But her most important song was one called “Strange Fruit,” which was very controversial because it was about lynching black people down South. Nobody wanted to hear this song. When Billie introduced the song at the Café Society, nobody wanted to be reminded about what was happening in our America of 1939, and nobody would record “Strange Fruit.” Even her great producer at Columbia Records, John Hammond, wouldn’t touch it. She was frustrated, so she turned to her friend, my Uncle Milt. And he told me years later she sang it for him the first time a cappella. Can you imagine that? That aching voice and that aching lyric. “Southern trees bear a strange fruit, blood on the leaves and blood at the root, black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze. Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees . . .” He told me, “Billy, I cried like a baby. And I said to her, ‘Lady Day, listen, I don’t care if we sell one record. People must hear this song. They’ve got to hear this song. We’ve got to get this made somehow.’” So they worked out a special arrangement with Vocalian Records, and Billie Holiday, a great black jazz artist, and my Jewish Uncle Milt together recorded “Strange Fruit” a song about lynching down South, the song that Time magazine in December of 1999 would call the song of the century. I’m so proud to say it’s on the family label, the Commodore.

As musical tastes changed, Jack watched his record business fade. His store was swamped by the emerging wave of large record chains taking over the industry.

Jack’s life would never be the same. Neither would Billy’s. And too soon, his father, lost, unsure of his next steps in life, was gone.

Crystal writes about “The Otherness” the weight one carries around after the loss of a loved one. He was sixteen, and real life had had its way with him far too soon:

I called it the “otherness” because that’s how I felt. I wasn’t here. I wasn’t there. I was in an other place. A place where you look, but you don’t really see, a place where you hear but you don’t really listen. It was “the otherness” of it all.

He struggled. His mom struggled.

Eventually, with the support of extended family—particularly his Uncle Milt, who became a powerful record producer—Crystal found his way to comedy, something he always knew he wanted to do even as a kid.

You won’t read tales from the sets of “Soap” or “Saturday Night Live” here. Crystal’s book isn’t about fame and fortune.

It’s about family, and change, and loss. And it’s a great read.

Highlights from “700 Sundays”

CHAPTER 1

the gray-on-gray Plymouth Belvedere was outside, gleaming under the streetlight, as best a gray-on-gray Plymouth Belvedere can. We were having the time of our lives. In other words, a perfect time for something to go wrong.

Big John Ormento was one of the local Mafiosos in Long Beach.

he came roaring up Park Avenue, swerved and slammed into the back of the Belvedere, which then slammed into the back of the car in front of it, reducing our new car to a 1957 gray-on-gray Plymouth Belv! The crash was tremendous.

Ormento ran to his car and took off.

Ten minutes later, Officer Miller was questioning my father. “Did you see who did this, Mr. Crystal?” Dad never hesitated. “No, we heard the crash, and by the time we got out here, they were gone.”

The twisted piece of metal sat in front of our house, at 549 East Park in Long Beach, Long Island.

It was a wonderful place to live.

Big John Ormento was in the doorway.

“I talked to my ‘friends’ and they told me you didn’t tell the cops nothing. So I want to make it up to yous.”

“What I’m trying to say is this, Mr. Crystal. I want to buy you a new car, any car you want, the car of your choice.”

Two weeks later, the car came back. Well, Big John knew a lot about bodywork because the car looked great,

That was my dad. He worked so hard for us all the time. He held down two jobs, including weekend nights. The only day we really had alone with him was Sunday.

I couldn’t wait for Sundays. He died suddenly when I was fifteen. I once calculated that I had roughly 700 Sundays. That’s it. 700 Sundays.

CHAPTER 2

Now you can’t pick the family that you’re born into. That’s just the roll of the dice. It’s just luck. But if I could pick these people, I would pick them over and over again because they were lunatics. Fun lunatics. What a crazy group of people, and great characters too. It was like the Star Wars bar, but everybody had accents.

One man was responsible, and he unknowingly changed my life. It was my Uncle Milt Gabler.

CHAPTER 3

For years and years, my grandfather had this little music store on 42nd Street between Lexington and Third that he called the Commodore Music Shop.

during the summer months, he rented this little cottage on the ocean, a place called Silver Beach in Whitestone,

Under those summer moons, my mom fell in love with dancing, and my Uncle Milt fell in love with the music, with the hot jazz.

one day, with the music in his mind, he takes one of the speakers from one of the radios, puts it over the front door transom of the Commodore Music Shop and dials it into the local jazz station

“Pop, listen. We can sell jazz records. Everybody’s coming in and wanting these jazz records, Pop. We should sell jazz records.” “Milt, why do I want to get involved with that crap for?” “We could make a couple of bucks.” “Okay. I’m in.”

they start licensing the master recordings of out-of-print records from some of the local record companies in town, and they start reissuing these out-of-print records with just a plain, white label that said “Commodore” on them. And these reissued jazz records started selling really well.

Milt starts going to Harlem and meeting all the great musicians in town from New Orleans, Kansas City and Chicago, all of these great original jazz giants, who play the same music but with different styles. And he gets another idea.

I want to produce my own records. Why are we making money for everybody else with these reissues for? I want to make my own jazz records, Pop. I can do it.”

the Commodore jazz label is born, the first independently owned jazz label in the world, and the records do great.

He decides to sell the discs by mail, so he starts something called “The United Hot Record Club of America.” He invented the mail order business in the record industry.

my father was now managing the Commodore Music Shop and he had become the authority on jazz and jazz records in the city. And this little store—it was only nine feet wide—was now the center of jazz not only in New York City but in the world, because that little mail order business was now third worldwide behind Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward,

Dad put on concerts wherever he could, Rye Playland, an amusement park, on aircraft carriers for the Navy, even Carnegie Hall,

One of Dad’s regulars, Conrad Janis, who is still a great trombone player, told me that Dad was the “Branch Rickey” of jazz.

It meant my dad was one of the first producers to integrate bands, to play black players with white players.

he had to do was emcee the show.

When I used to host the Grammy Awards, I would think that somehow I was channeling him, because I was doing the same thing he did decades before

Of all the great people who were recording for my uncle and being produced in concert by my dad, Billie Holiday was by far the greatest.

I was so blessed to be in her presence

But her most important song was one called “Strange Fruit,” which was very controversial because it was about lynching black people down South.

nobody would record “Strange Fruit.”

So they worked out a special arrangement with Vocalian Records, and Billie Holiday, a great black jazz artist, and my Jewish Uncle Milt together recorded “Strange Fruit” a song about lynching down South, the song that Time magazine in December of 1999 would call the song of the century. I’m so proud to say it’s on the family label, the Commodore.

CHAPTER 4

Heroes don’t have to be public figures of any kind. Heroes are right in your family. There’s amazing stories in all of our families, you just have to ask, “And then what happened?”

CHAPTER 5

May 30, 1956. Dad takes us to our first game at Yankee Stadium.

Dad took out his eight-millimeter camera to take movies so that we would never forget. But how could you? How green the grass was, the beautiful infield, the bases sitting out there like huge marshmallows, the Washington Senators in their flannel uniforms warming up on one side, and the Yankees taking batting practice on the field. The first time I heard the crack of the bat. It was so glorious.

That’s all I wanted to be . . . a Yankee. Then on Sundays, Dad would take us out to the Long Beach High School baseball field to teach me how to hit the curveball, which he had mastered.

Wait on it. Watch it break, and hit it to right.

Remember that program Mantle signed in 1956? Well in 1977, I was on Soap, playing the first openly homosexual character in a network show, and ABC had me appear on every talk show. I called it the “I’m not really gay tour.” Mickey was a guest on the Dinah Shore show, and I brought the program, and he signed it again, 21 years later. We became good friends,

When Mickey died, I thought my childhood had finally come to an end.

CHAPTER 6

They were very affectionate with each other. Always holding hands in front of us, a kiss on the cheek, arm around each other. It was always nice to feel that your parents were still in love.

on Saturday nights in the Catskills, the comedian is the king. I had never seen a comic in person before.

I have this epiphany. I say to myself, I could never play baseball like Mickey Mantle ever, but this I could do. I memorized his act instantly.

The next weekend, all the relatives were coming over

I took the comic’s act that I’d just seen, and I changed it just a little bit to suit my crowd.

Oh, my God. I ran to my room. The laughter went right into my soul. Oh, it felt so good. Destiny had come to me.

“Pop, listen. I want to be a comedian. Is that crazy? I loved it. I just loved it. I want to be a comedian.” “Billy, it’s not crazy because I think you can be one, and I’m going to help you.”

CHAPTER 7

That’s how you really start. You want to make your folks laugh.

At the end of Long Beach, in a place called Lido Beach, about two miles or so from my house, was a Nike missile base. Every day at noon the air raid alarms would go off and the Nike missiles would rise up and point to the sky.

flatbed trucks with new missiles on them would pass us.

Uncle Milt always made sure to take the time to tell me something that would inspire me. He never discouraged me. Never said, “It’s a tough business. Have something to fall back on.” He always made me feel that I could be funny anyplace, not just the living room.

If you want to be a performer, great, but try to do a lot of things. Not just one thing. Watch Sammy Davis, Jr.”

I watched Sammy every chance I got, never once thinking that someday I not only would become his opening act, but that I would also become Sammy Davis, Jr.

The stories he would tell were priceless. He was mesmerizing. Listening to his history and firsthand accounts of the biggest stars in the business was simply sensational . . . that’s how I developed my impression of him. I couldn’t help but absorb him, and many a night I would leave his dressing room with his sound, his inflections, his “thing,” man, ringing in my head.

CHAPTER 8

October 15, 1963.

My parents came into the kitchen to say goodbye. They were on their way out to their Tuesday night bowling league at Long Beach Bowl. They loved bowling with their friends. They had so much fun doing it. And frankly, this was pretty much the only fun that they were having now because times had changed for us, and not for the better.

The Commodore Music Shop had closed a few years earlier. It couldn’t keep up with the discount record places that were springing up

And the bands that I loved, were replaced now by the Duprees, the Earls, the Shirelles and the Beach Boys.

My dad now was fifty-four years old, and he was scared. With Joel and Rip away at college, he was out of a job. Oh, he did the sessions on Friday and Saturday nights, but he gave most of that money to the musicians to keep them going. Dad was also closing down the Commodore label, working out of the pressing plant in Yonkers. It was so sad to see him struggle this way. Nobody wanted to hear this music anymore.

Dad was exhausted, and sad. Jazz was his best friend, and it was dying, and he knew he couldn’t save it.

Don’t you understand what’s happening here? I don’t know how I’m going to be able to send Joel and Rip anymore. You’re going to have to get some sort of scholarship or something.” He continued, the intensity in his voice growing. “Look at you moping around. This is all because of that goddamn girl, isn’t it?” I snapped, “What the hell do you know?” It flew out of my mouth. I never spoke to him like that.

I felt awful. Oh, why did I say that? I ran after him to apologize, but they were in the car and gone before I could get there. I came back to the kitchen thinking, okay, calm down, they’ll be home around 11:30, quarter to twelve. I’ll apologize then,

I was startled by the sound of the front door opening, and I looked at the clock, and it was 11:30, just like always, and I could hear Mom coming down the hallway

The door flew open. The light blinded me, further confusing me, and she was on me in a second. “Billy, Billy, Daddy’s gone. Daddy’s gone. Daddy’s gone.”

Dad had a heart attack at the bowling alley and he didn’t make it. They tried to save him, and they couldn’t.

It was as if someone had handed me a boulder, a huge boulder that I would have to carry

around for the rest of my life.

Uncle Milt was great that night. He took charge, taking care of his sister, helping her make all the funeral arrangements.

CHAPTER 9

The next day the strangest thing happened. The car wouldn’t start. The gray-on-gray Plymouth Belvedere refused to go. He had driven this car a hundred miles a day every day for all the years that he had it. He took perfect care of it. It never failed him until this day. It knew that he was gone, and it refused to go without him—it just stood in the driveway with the hood up.

The last thing my dad did on earth was make the four, seven, ten. It’s a tough spare to make, and he was so happy. “Whoa, Helen. Look at that. What a day . . .” And he dropped dead, just like that.

CHAPTER 10

Then after everybody’s gone, you’re left with it. You’re left with the shit of it, the size of it, this opponent in your life, this hole in your heart that you can’t possibly repair fast enough. And the first thing that happens to you is you get angry. You get so mad that this has happened to you at this point in your life, you want answers. I was so furious I could storm right into God’s office.

But then I developed something else. The best way I can describe it is by what I called it. I called it the “otherness” because that’s how I felt. I wasn’t here. I wasn’t there. I was in an other place. A place where you look, but you don’t really see, a place where you hear but you don’t really listen. It was “the otherness” of it all.

Basketball tryouts. The sign was posted in the hallway. I wanted to be on the varsity basketball team.

It was probably too soon for me because the first day of tryouts, somebody threw me the ball, and it bounced right past me. I just couldn’t see it. I would dribble the ball off my foot because I was in some other place. The otherness was blinding me.

After the third day of this, the coach, Gene Farry, called me into his office after practice, I thought to cut me. Instead, he asked me something that nobody had asked me since October 15. “Bill, are you okay? How’s everything at home?”

I stared at him, unable to speak. Suddenly, tears welled up in my eyes. I just exploded . . . the words, making their way out of my heart . . .

Coach Farry, only twenty-four at the time, smiled at me, and said, “Take all the time you need, I’ll be out here.” He put me on the team. That’s the nicest thing anyone has ever done for me.

CHAPTER 11

Mom had “a plan.” She started taking the train in from Long Beach into Manhattan round-trip every day. An hour each way, a tough commute for anybody. But when you’re fifty and you’ve got that boulder to carry around, it’s a little tougher. Her plan was simple. She began to study at a secretarial school, to learn shorthand, typing and dictation so she could get a job as a secretary.

she got a job, not just as a secretary, which would have been fine. She got a job as an office manager in Mineola, Long Island, at a Nassau County psychiatric clinic,

I graduated high school, and soon I would go away to college. Mom had put aside $2,500 so I could go. That may not seem like a lot to you, but she was only making $7,500 a year.

I got down to Huntington, West Virginia, and the first day of school was a total disaster. They cancel the freshman baseball program because of a funding problem. This was years before freshmen could play varsity, so that was it, there would be no baseball for me. Suddenly, I’m simply a Jew in West Virginia.

one day I got a package in the mail, which totally confused me because it was the only package I got all year that didn’t have a salami in it. It was from California: Hollywood, California. I didn’t know anyone in California. I’d never been to California. The furthest west I’d ever been was Eighth Avenue at the old Madison Square Garden. I opened it up and it was a book from Sammy Davis, Jr., who I had never met. Uncle Milt had been

recording him. He did Sammy’s first gold record, “Hey There” from The Pajama Game. A note from Uncle Milt was attached to the front of the book. It said he had written to Sammy about me. He told Sammy that he thought that I had something, but that I also had “the otherness.” He signed it as he signed all his letters to me, “Keep thrillin’ me, Uncle Milt.” I opened it up, and Sammy had signed the book to me. I could hear his voice as I read: “To Billy, you can do it, too. The best, Sammy Davis, Jr.”

I came home for the summer of l966, and got a job as a counselor in a day camp at the Malibu Beach Club in Lido Beach. One day after work, I was on the beach with my good friend Steve Kohut, and this really cute girl in a bikini with a fantastic walk goes by, and I said, “Who’s that?” “That’s Janice Goldfinger,” Steve said. “She just moved here.” I said, “I’m going to marry her.”

Four years after I told Steve Kohut, “I’m going to marry that girl,” I did. After Janice and I got married in 1970,

CHAPTER 12

The last story would start on Halloween night of 2001. Once again, the entire country had the otherness. Our family was still reeling from the loss of Uncle Milt in late July, and Uncle Berns was having a very difficult time.

But on this Halloween night, the ghosts and goblins were just kids on the street as I passed them on my way to Game Four of the World Series.

my cell phone went off. It was my brother Joel. “Billy, listen. We have a big problem. Mom had a stroke.” “What?”

These strokes are nasty characters. They’re mean. It’s a mean illness. A little bit of progress like that, and then many steps back. Some days you’d have a smile on your face, and the stroke would know it, and it would

slap your other cheek. It’s a mean, cunning, nasty illness.

She didn’t know me as her son. These strokes are like bank robbers. They break into your vaults and steal the things that you treasure most, the things that are most valuable to you, your memories. They steal your life. But then she rallied, like I knew she would.

I went into great detail how the show worked

for me, where the laughs had flowed, and she just simply stopped me and said, “Billy, dear, were you happy?” “Yeah, Mom, I was.” “Well, darling, isn’t that really all there is?”

And that’s the last time we spoke. The next day the bank robbers broke in again. This time they stole her.

She rests next to Dad, and even in my sorrow, I found some comfort in the fact that they were together again, in their same bed positions, quiet and peaceful, just like I saw them every morning of those 700 Sundays.

I don’t know why I thought it would be easier this time. I was fifteen the first time. Fifty-three the second. The tears taste the same. The boulder is just as big, just as heavy, the otherness just as enshrouding.

We sold the house. We had to. Without her in it, it really didn’t make much sense to keep it. Somebody else owns it now, but it doesn’t belong to them . . . because I can close my eyes and go there anytime I want.

700 Sundays is not a lot of time for a kid to have with his dad, but it was enough time to get gifts. Gifts that I keep unwrapping and sharing with my kids. Gifts of love, laughter, family, good food, Jews and jazz, brisket and bourbon, curveballs in the snow, Mickey Mantle, Bill Cosby, Sid Caesar, Uncle Berns

You can pick up “700 Sundays” at Amazon.