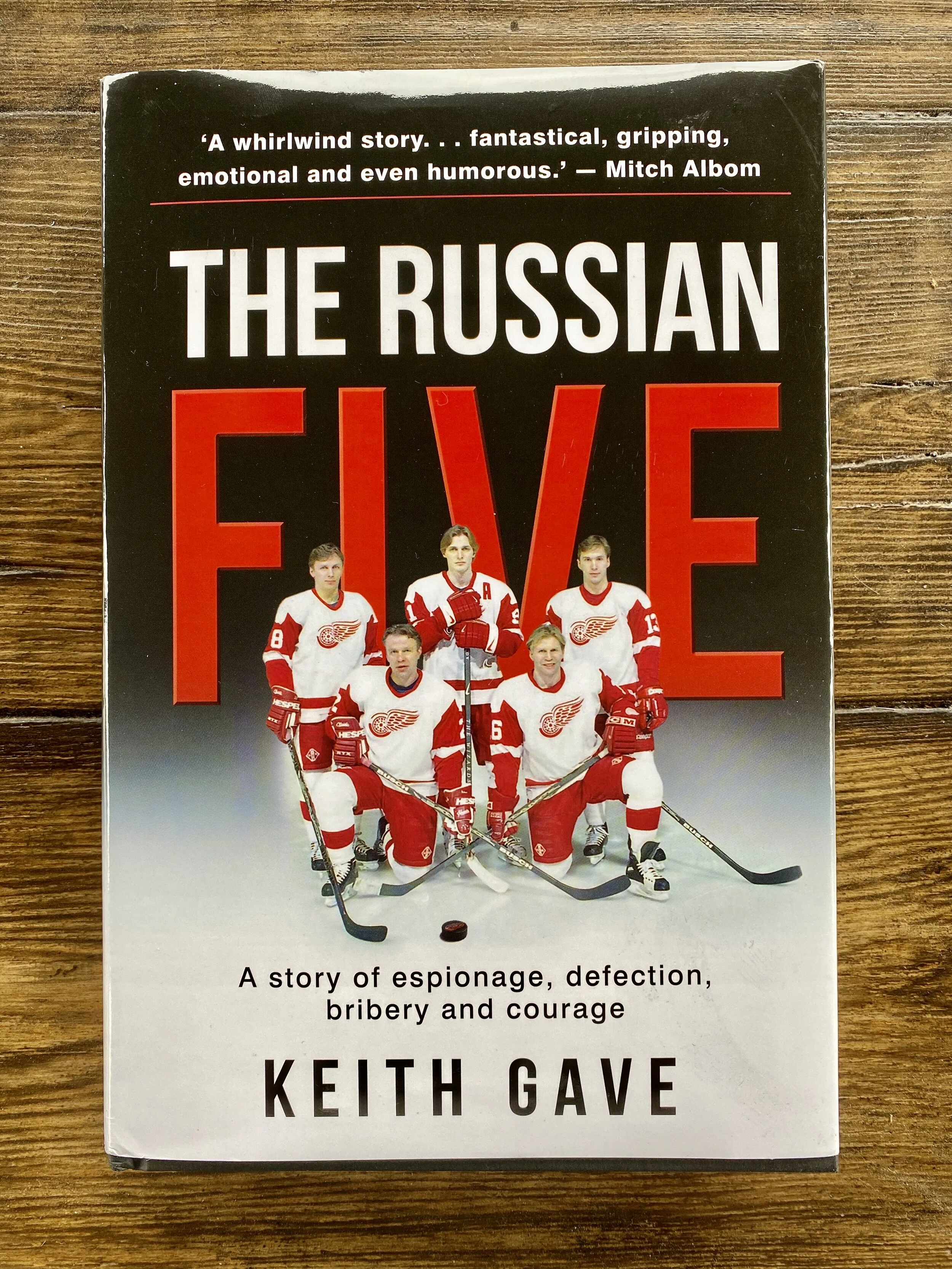

Lessons From “The Russian Five” by Keith Gave

As kids, my friends and I half-skidded, half-staggered across a variety of perilous and uneven ice-covered surfaces: the parking lots, streets, and playgrounds of mid-Michigan. We played something resembling hockey. There weren’t any youth leagues in our town then, so we made our own, complete with goals carved into snowbanks.

And we impersonated our heroes, the best players from our favorite team: The Edmonton Oilers.

Edmonton?

Yes, of course. The Oilers were the best, with Wayne Gretzky, Paul Coffey, Jari Kurri, and Grant Fuhr in goal.

We paid no attention to our state’s team, the Detroit Red Wings, because they were awful, and better known as “The Dead Things” in the mid-1980s.

“The Russian Five” is about how all of that changed: how the Red Wings built a transcendent and lasting success out of the ashes of the Dead Things era.

It wasn’t easy. It wasn’t conventional. And it certainly wasn’t linear, with fits and starts, advances and retreats, and adjustments and alterations on the way to title contention and, eventually, Stanley Cup championships.

Much more than a nostalgia trip, “The Russian Five” is a book about creativity, boldness, and perseverance in the face of criticism and uncertainty. It’s about operating without a road map and pressing on anyway.

In other words, “The Russian Five” is a book about how to build something great.

Espionage on the ice

The author, Keith Gave, is uniquely qualified to write this book. After all, he had an insider’s view as the Red Wings beat writer for the Detroit Free Press.

But the beat writer’s job wasn’t Gave’s only advantage.

Gave previously worked as a Russian linguist for the National Security Agency. And, without crossing ethical lines, he earned an assist by helping the Red Wings get two transformational players out of the Soviet Union.

Gave was propositioned by Red Wings executive vice president Jim Lites to pass along a message to Sergei Federov and Vladimir Konstantinov:

“You know hockey, you know the league, and you know us,” Lites said. “And as a member of the media, you can get access to those guys when nobody else in the NHL can. All we’re asking for is that you make that first contact for us. We can take it from there - if it’s going to happen - but we can’t do anything without that initial contact.”

While covering games in Helsinki, Finland, Gave was able to slip letters, tucked into media guides, from the Red Wings to the players—even as the KGB watched nearby. It was the opening salvo in what would become a pipeline of talent from the Soviet hockey team to Detroit.

Lessons learned

The Red Wings management, owner Mike Illitch, executive vice president Jim Lites, and general manager Jim Devellano, desperately wanted to revive the proud franchise, which bottomed out in the 1980s.

And we can learn from that time--from looking at the bold strategies and actions the Red Wings took--and apply them to our own work and lives today.

The standard approach wasn’t working

The Wings were building up, slowly, in the usual hockey fashion: by drafting North American players and adding a free agent here and there.

But the well-worn path wasn’t working, or wasn't working fast enough:

“But building through the draft is a painfully slow process, and it comes without a guarantee. It takes immense patience and more than a little luck -- borne through years of scouting and stockpiling and developing players who were teenagers barely shaving when they were drafted onto their NHL teams.”

If the Red Wings were going to succeed, the leaders would have take a new, unconventional, and even potentially dangerous path to tap a vast reservoir of previously unavailable talent.

“The quickest way to catch up, Devellano was now convinced after numerous briefings from Smith, was to begin drafting Europeans, especially those groomed behind the Iron Curtain.”

In 1989, the Red Wings selected Sergei Federov in the fourth round of the NHL draft. Using a high pick on a Soviet player just wasn’t done, because there was no precedent for getting a player out of the country and into the NHL.

Eventually, through defections and trades, the Red Wings would assemble five extremely talented players from the Soviet Union national team, reuniting them in Joe Louis Arena where they would eventually win a cup together, and kick off a enduring run of excellence. Forwards Sergei Fedorov, Igor Larionov and Vyacheslav Kozlov, and defensemen Vladimir Konstantinov and Viacheslav Fetisov ,brought the Stanley Cup back to Detroit.

No one succeeds alone

Bringing the Russian players to Detroit required a lot of help from both inside and outside the Red Wings organization.

Scouts had to implore Devellano to take that first bold step, drafting Federov in the fourth round in 1989.

Keith Gave delivered the opening communication to Federov and Konstantinov.

And the Wings needed a man on the inside, someone close to the team that would help convince the players to leave and guide them through their defections:

“There, Lites met a man pushing 50, a Russian ex-pat who had left his country when he was in his 30s. Because he spoke Russian, French, and English, the Soviets used Ponomarev as their official photographer whenever they are in North America or Western Europe. “I can talk to the guys for you,” he told Lites, who was beginning to feel like he could make the kind of deal that would pay enormous dividends for the Red Wings.

“As Mike Illitch told me over and over and over, always close,” Lites recalled. “So I sat there and said, ‘Let’s talk. If we do this, you have to work for me. I have to know your loyalties are to us.’ Their handshake deal was followed up with a written contract that said the Detroit hockey club would pay Ponomarev $35,000 for a successful defction of Sergei Fedorov or Vladimir Konstantinov.

‘And Michael, from that day on, was my guy. That’s how all this started.’

Success is always a team effort.

Let talented people flourish

Scotty Bowman is arguably the greatest coach in NHL history. He won nine Stanley Cups between 1972 and 2002, amassing 1,244 wins—more than any NHL coach in history.

Bowman was tough, demanding, and a control freak. But even he knew when to let talent flourish, such as when he put all five Russian players together on the ice.

As captain Steve Yzerman recalled:

“When (Coach) Scotty (Bowman) put them all together, the five Russians, there was instant chemisry,” he said. “It was unique. It had never been done in the NHL, and for us it was enjoyable, really enjoyable to watch, and obivously it helped us win hockey games.”

Slava Kozlov:

“Our biggest privledge was that the coaches didn’t touch us or try to teach us how to play hockey,” Kozlov said. “We were amongst ourselves and would talk to each other. I was actually shocked by the other guys. I adjusted not to what the coaches were saying but to what the guys were saying. I would do everything that my older partners told me.

[...]

Kozlov spoke without an ounce of bravado. Conceit, arrogance self-aggrandizement -- whatever you care to call it -- just isn’t in his DNA. Like theothers in the Russian Five unit, he was a “Master of Sport” in the Soviet Union -- and had the medal to prove it. When he said the coaches just let them play their game without getting in the way, he was merely confirming the same truth that Scotty Bowman spoke.

Strong leaders know when to let those they lead take the forefront--and everyone reaps the rewards.

Perseverance is critical: the journey is never linear

The Red Wings eventually became extremely successful--in the NHL’s regular season. But the playoffs continued to disappoint:

The Red Wings had begun a new season in the autumn of 1996 with a cloak of despair draped over the team. The fans sensed it, gripped by a malaise that was starting to feel comfortable. No longer were they giddy with hope and expectations. They had grown disillusioned after four straight spring times wrought with profound disappointment. Beyond wary, they were building a barrier around their hearts to keep them from being broken yet again.

Players, too. Captain Steve Yzerman was beginning to doubt that it was in the cards to have his name engraved on the Stanley Cup.

But the Red Wings did break through, hammering the Philadelphia Flyers in the 1997 Stanley Cup Finals, and rallying around a statement-making check by Konstantinov on the Flyer’s Dale Hawerchuk:

Hawerchuk, a Hall of Famer, left the ice, didn’t return, and retired after the series. Konstantinov’s hit—a clean check—was a clear declaration that 1997 would be different for the Red Wings, who went on the win the Cup.

Remember to savor the journey

Just six days after the Red Wings finally won the cup, tragedy struck.

Returning from a night out with his teammates, Vladimir Konstantiov and Slava Kozlov were in a horrible limousine accident.

“There’s been an accident,” he said, explaining that the caller was an officer from teh Oakland County Sheriff’s Department. No one said a word. Instead, they clusgterred aroudn their captain, who stuck a finger in his ear to block teh surrounding noise.

[...]

The Stanley Cup, until that moment the epicenter of their universe, was quickly forgotten. Ignored. Reudced to a gratuitious postscript.

Koslov recovered. Konstantinov survived, but would never play hockey again. Today he lives in Detroit and continues his therapy, more than 20 years later:

Ten months later, on an unseasonably warm March day, “the greatest hockey player in the world” lurches into the living room of his town house in suburban Detroit, grasping a walker. He has returned from a visit to his doctor and is accompanied by one of the nurses who provide round-the-clock assistance. He plops into a chair at a table off the kitchen to play a card game, Uno, with a Russian-speaking nurse. Irina Konstantinov says her husband really likes Uno. “The left frontal lobe,” she starts. “It handles executive functioning, where a person analyzes their own behavior, determines whether it’s right and appropriate. That he doesn’t have. Destroyed. He can’t process idealistic feelings about life, like love of country or happiness that his child is graduating. Everything for him is matter of fact.”

Photo: Det News

Chasing goals is great. But we have to remember to enjoy the climb as well. We never know what lies ahead.

Konstantiov’s legacy endures. The Wings became the gold standard in the NHL, winning championships in 1997, 1998, 2002, and 2008. His toughness and perseverance as detailed in “The Russian Five” is something we can all draw inspiration from.

“The Russian Five” is a fun and valuable read for any hockey fan

At times, Gave’s book reads like a 007 spy thriller, as the Wings schemed and smuggled players out from behind the Iron Curtain. At other times it’s a book about leadership, teamwork, tragedy, and belief in the face of uncertainty.

In any case, it’s much more than a sports book.

The Russian Five is a great retelling of the strategy, struggle, victory, and calamity of the Detroit Red Wings’ climb to greatness. The book’s lessons are applicable to all of us as we half-skid, half-stagger our way across the uneven and slippery surfaces of life.

You can pick up “The Russian Five” by Keith Gave at Amazon.